Last Updated on January 18, 2022 by rob

Detective Noboru (Koji Yakusho) investigates the killing of a woman found drowned in a puddle of salt-water. As more victims are murdered in the same manner Noboru finds himself haunted by a figure in a red dress (Riona Hazuki) accusing him of her death. But when the victim’s killer turns out to be her ex-boyfriend Noboru realises that the vengeful ghost is connected with old memories of a ferry trip he used to make past an asylum in which inmates who broke the rules were drowned in a basin of salt-water.

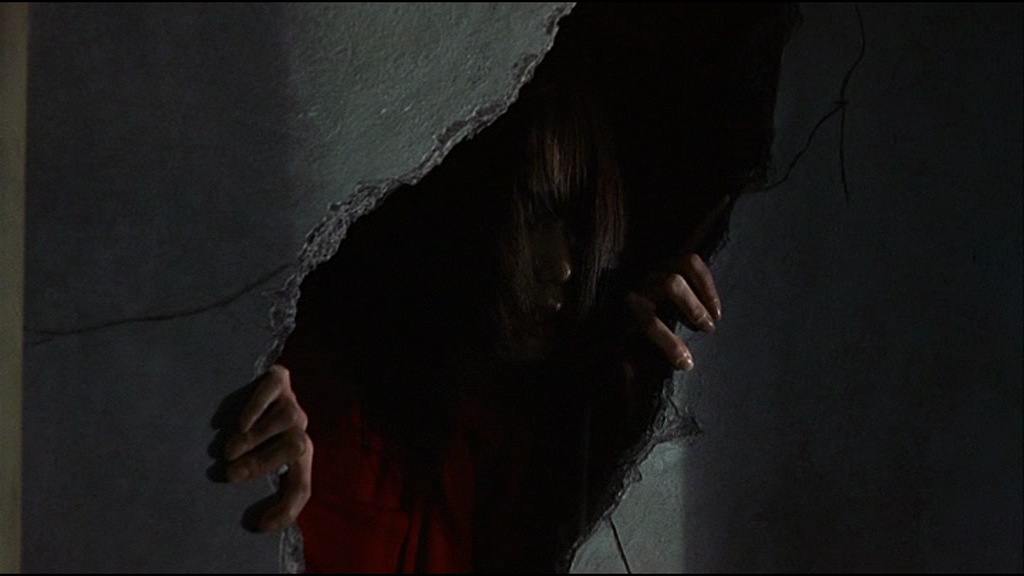

I liked this hybrid of police procedural and ghost story. The director seems to be reworking plot elements of his earlier hit Cure. Once again Koji Yakusho plays a stressed out detective, once again he’s investigating a series of unusual murders and once again he finds himself at the centre of a grim, climactic plot twist involving the sole woman in his life, Harue (Manami Konishi). But Kurosawa’s notion of ghosts (for there is indeed more than one ghost here) who are vengeful and sorrowful yet capable of forgiveness toward the living is original enough to hold its own in the post-Ring wave of Japanese ghost stories. After reflecting on the film you realise the ghost – in the shape of a lady in red equipped with a piercing scream whose presence is foreshadowed by an earthquake like shaking and rumbling (interestingly, Kurosawa used a similar motif in Cure) – is really the main protagonist here. But because the story is told from the perspective of one of her victims it takes a while for the penny to drop.

Retribution avoids the somewhat clipped, elliptical storytelling style of Cure and for that reason alone it’s an easier, more straightforward watch. But on the other hand despite good performances and setpieces Kurosawa’s interest in the psychological aspects of his characters flounders in his effort to link Noboru’s faulty memory (on which the film’s biggest plot twist hinges) with a theme about how people are blind to changes around them. This feels too weakly conceived to really pack the oomph it needs. Still, I really enjoyed the ambition on show just in terms of showing the ghost. There are moments (such as the ghost seemingly peeking out from behind a fence) that could strike one as unintentionally hilarious but I thought it worked really well because – succeed or fail – there’s something exhilarating about watching a director performing a hire wire act like this, trying to find new ways to depict a ghost on screen.

Kurosawa is greatly assisted by Akiko Ashizawa’s atmospheric cinematography which includes some subtly off kilter compositions that evoke an effective sense of unease. And the director’s lengthy single takes really pay off in sequences such as a police interrogation in which a murder suspect starts to see something in the room none of the others can. I also loved the scene in which our ghost first appears in Noboru’s flat – gliding toward the detective with a ghostly shriek as he dives out the way – as Kurosawa audaciously keeps the shot, with both figures just a few feet apart from each other, running and running and running. He doesn’t allow the viewer the implicit emotional release of a cut to another angle so it’s a cracking moment of delirious tension because you’re watching this and thinking “What the fuck is going to happen now?!”

And I’m always amused by the absurdist tone Kurosawa can’t but help bring to his work. As when Noboru simply turns up at some seafront wasteland and pulls a bag full of evidence from a muddy puddle without any explanation as to how he knew it was there! The director’s fondness for old and worn locations is familiar from Cure but the large interior spaces on show here (such as the police HQ) represent something newer and evoke a fascinating emotional texture. In an odd way it sort of reminds me of the original Blade Runner – this juxtaposition of modern people and technology in locations that look aged and denuded. Yakusho – looking much scruffier and unkempt here than he did in Cure – brings a volatility to his character that absolutely sells the idea he’s struggling with something unpleasant in his past.

As it turns out, the root of Noboru’s short-temper is a forgetfulness that’s turned into negligence and then – as the ghost possesses the bodies of its victims – something very much worse. What that something is turns out to be a real shocker but it works because in retrospect the clues are all there. Ryo Kase (Baron Nishi in Clint’s Letters From Iwo Jima) has a minor supporting role as Noboru’s partner but of all the supporting cast the one I was most taken by was Manami Konishi as Noboru’s wife, Harue. It’s a quietly compelling performance and her attitude – placid, distant – makes perfect sense once you’ve seen the film, hinting at something not quite right en route to the film’s surprise twist ending.