Last Updated on January 22, 2021 by rob

In Tokyo a string of murders in which all the victims have ‘X’ carved into their body convinces Detective Takabe (Koji Yakusho) that the killers may have been hypnotised. When a young man with unusual powers of suggestion named Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara) is arrested on suspicion his connection with an early 20th century hypnotist named Mesmer is discovered. As Takabe finds himself drawn to the derelict site of Mesmer’s experiments he discovers the secret of Mamiya’s power and with it his own destiny.

A crafty psychological thriller this and very cunningly constructed. The first half comes on like a police procedural but once Mamiya is captured the second half turns into this clipped, elliptically told tale with Kurosawa pushing the viewer to put the pieces together themselves. But it’s not as if the director doesn’t play fair by the viewer. He supplies plenty of clues. When Detective Takabe, burdened with having to care for his mentally ill wife, recoils in horror at a vision of her hanging dead in their kitchen it’s Mamiya who somehow knows what he’s seen and understands what it portends. Takabe’s psychiatrist pal Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki) ventures the ominous suggestion that Mamiya has come as a missionary to propagate a ceremony and missionaries, as we all know, seek converts.

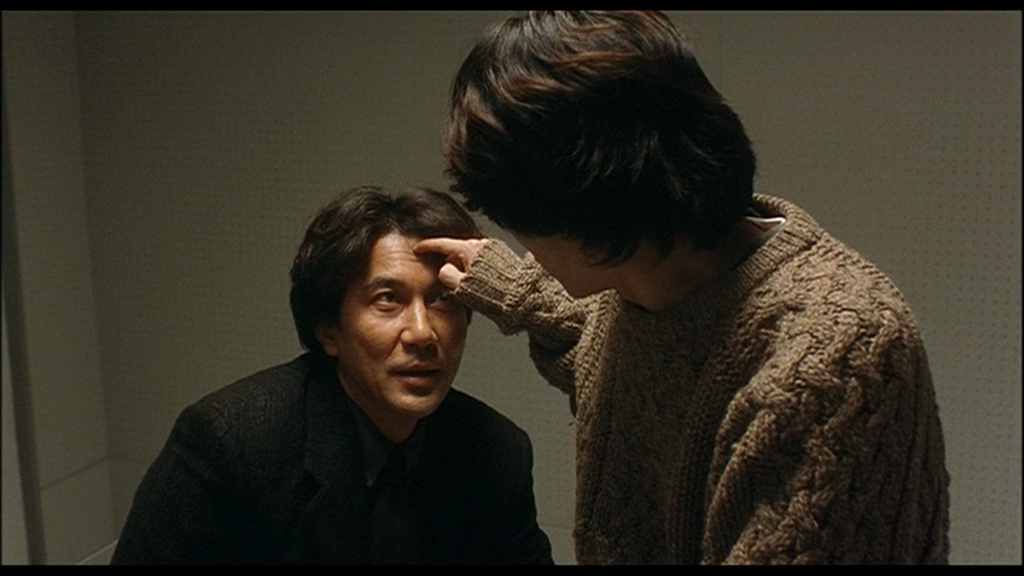

The introduction of a magical incantation into a contemporary setting (a tactic which predates Hideo Nakata’s much better known Ring by a couple of years) leads to a sucker punch of an ending – at least if you’re unfamiliar with the film’s opening reference to Bluebeard. It’s aided in no small part by Kurosawa’s marvellous dialogue, particularly that of the villain Mamiya, whose infuriatingly circular exchanges with everyone he encounters (delivered with maddening calm courtesy of Masato Hagiwara’s superb performance) take on the aspect of a chant, a mantra. Like the cobra’s sway it’s his way of lulling his victims into a trance so he can strike. By the time the interrogation scenes between Takabe and Mamiya come up we’re on the edge of our seat wondering if Mamiya may subliminally hypnotize Takabe into killing his comrades or worse.

As creepy as Mamiya’s performance is Cure really benefits from Koji Yakusho’s role as Detective Takabe. For the film to work it is essential we feel sympathy for this guy and in the domestic scenes with his wife Yakusho really sells the stress his character’s under as all attempts at trying to keep their relationship going founder. As a result the short fuse he displays in his encounters with Mamiya seem entirely understandable. We never doubt that this guy has anything other than his wife’s best interests at heart and once we accept that the director has us set up for a shocker of a twist. I suppose what Kurosawa is doing here is using a story about hypnotic suggestion to expose the true nature of ourselves. He’s very clever in the way he imbues the home scenes of Takabe and his wife Fumie (Anna Nakagawa, most effectively playing a character with memory loss so severe she cannot carry out simple domestic chores) with an existential chill.

Another scene in which Mamiya visits a local hospital for a checkup and lulls a female GP into a trance using nothing more than a spilled cup of water is a brilliantly executed variation on the film’s theme of what’s really inside us, one that pays off here with a moment of horrific gore. Equally striking are the settings as the action takes place in a carefully stylised landscape of urban decay. The director is excellent at using interior space and blocking the actors in the frame in ways that evoke a distinctly claustrophobic, subterranean feel. He shoots a chase between Mamiya and the police through the hallways of a dusty warehouse and makes them all look like lab rats in a maze.

And what exactly does the film’s title actually refer too? For me the most chilling aspect here is the gradual realisation of what Kurosawa is getting at. Why does Mamiya say, “There is nothing inside me” and tell Takabe that he alone grasps the true meaning of the oft repeated question he asks his victims, “Who are you?” Two pivotal moments here – both restaurant scenes featuring Takabe – in the first we see our hero so stressed out he can barely touch his food, in the second he’s polished off everything and relaxing with coffee and a cigarette. What’s changed in the interim? What burden has been lifted from Detective Takabe that he now seems so content? I think it really does send a bit of a chill down the old spine when you realise what Kurosawa is getting at.