Last Updated on January 22, 2021 by rob

Hayasaki (Koji Yakusho) the genius inventor of the world’s first artificial body is stunned when his own doppelganger turns up and offers to help clear away all the stresses in his own life so he can concentrate on his work. With the help of hired thug Kimishima (Yusuke Santamaria) and Yuka (Hiromi Nagasaku), a woman whose own brother has also been replaced by a doppelganger, the inventor’s dream of completing the world’s first artificial body edges closer to reality. However, both Kirishima and Hayasaki’s former boss have plans to seize his invention for themselves.

After grim horrors like Cure and Pulse this is a welcome change of pace for Kurosawa. It’s nominally a riff on the old Jekyll and Hyde theme but the director’s oblique approach to the subject matter means his characteristic thoughtfulness and urban chills sit side by side with a delightfully absurdist sense of humour and an unexpectedly sunny disposition toward his principal characters. The result is a charmer which tosses out riffs left, right and centre on the nature of the self and doppelgangers while spinning an entertaining yarn about a stressed out scientist who discovers that the answer to all his problems isn’t fame or fortune but a nice personable girl to go off and enjoy life with.

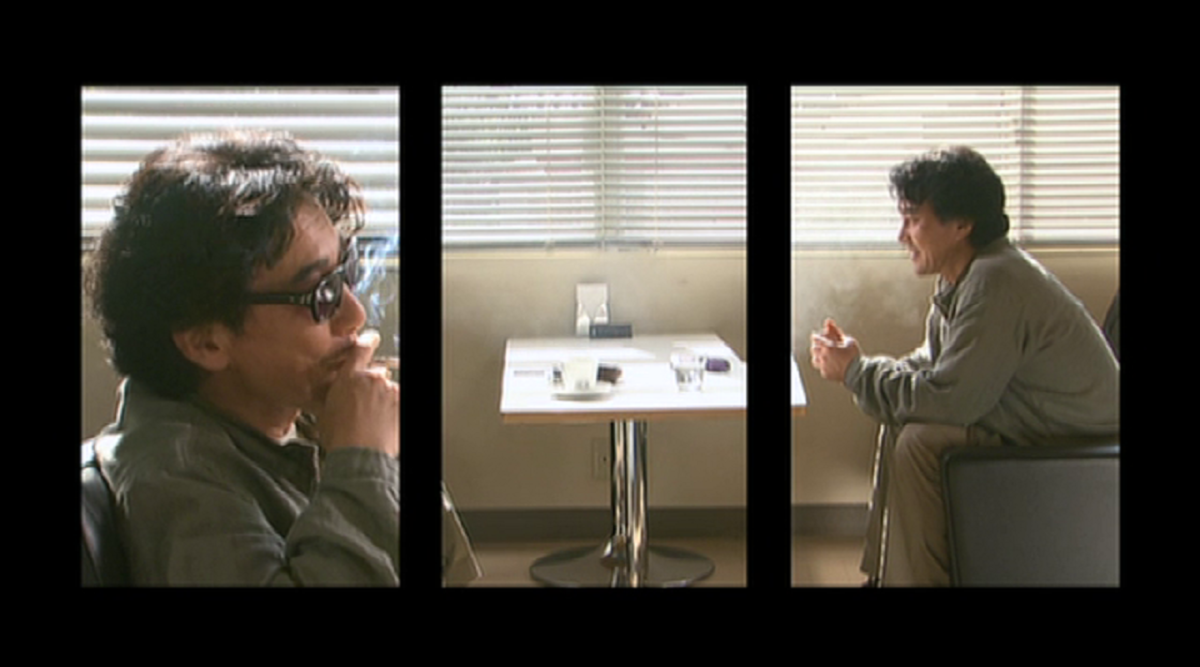

Koji Yakusho is clearly enjoying himself playing dual roles. His amoral double who gleefully steals, kills and even takes advantage of an unwary Yuko isn’t a monster revelling in chaos but a clever figure with a clear endgame in mind and he makes the character a likeable and unpredictable figure whom we’re actually rather sorry to see brutally finished off. And as the ‘real’ Hayashi he develops a nice kinship with another lost soul in Hiromi Nagasaku’s lonely Yuka. Part of the film’s appeal is that Kurosawa really doesn’t seem all that interested in the standard good and evil duality (he never even tries to explain how or where the doppelgangers have come from). The director plays around with it from a formal perspective – splitting the screen into separate panels when Hayashi and his doppelganger are conversing – but thematically he seems more interested in ringing the changes.

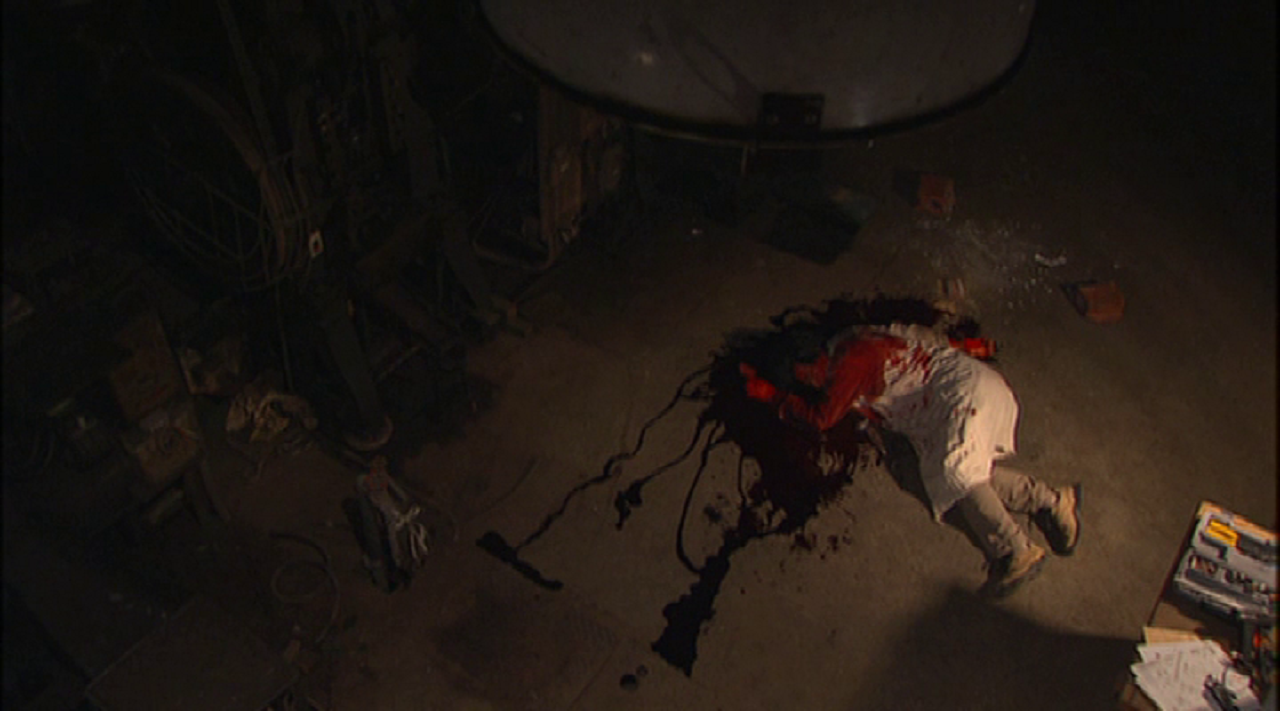

Typical of this is Yuka’s encounters with her brother’s double which turns into something unexpectedly positive. The original was a world class slacker but this new one, as Yuka approvingly tells Hayashi, spends all his time writing the novel the original brother promised to do but never did! It’s only when Yuka feels she’s being ignored by her sibling that Hayashi’s doppelganger steps in to solve her problem (in another of the director’s exemplary staged scenes of casual violence) by smashing the brother’s head in with a hammer. In scenes like this you can sense what Kurosawa is going for. The real theme of his story is about characters trying to find the right balance in their lives. The answer isn’t an obsession with work which as presented here enslaves Hayasaki and Yuka’s brother making them selfish and indifferent to those around them.

In fact everyone who desires to possess Hayasaki’s machine out of greed or power loses out or loses their lives. There are some of the director’s trademark chills here – most notably in the opening sequence as Yuka encounters her brother at a downtown store then returns to her flat only to find his doppelganger in place – but Kurosawa keeps undermining the unease with comic reversals and imbues later proceedings with a sort of bonkers optimism that proves infectious. By the time we get to the third act we’re into a splendidly comic road trip as Hayasaki and Yuko find themselves pursued by former allies who want the machine for themselves as the director works in all manner of amusing pratfalls and visual gags (chief amongst them is what looks like a Raiders of the Lost Ark homage with Kimishima pursued by an enormous inflatable beachball).

Amidst all this merriment Kurosawa’s point is that what really matters is having empathy for others, an empathy that in its own oddball way extends to machines. The film’s last scene is a lovely bit of business. On a clifftop overlooking the sea Hayasaki activates his sentient chair which – free of having to obey the demands of a human host – comes to life and, arms waving merrily, tootles straight off over a cliff! It’s a wonderfully absurdist image, this mobile chair with its mechanical arms waving in the air and yet oddly life affirming with it. All that’s left is for Hayasaki and Yuka to stroll off into the sunset together. Good for them.