Last Updated on September 29, 2020 by rob

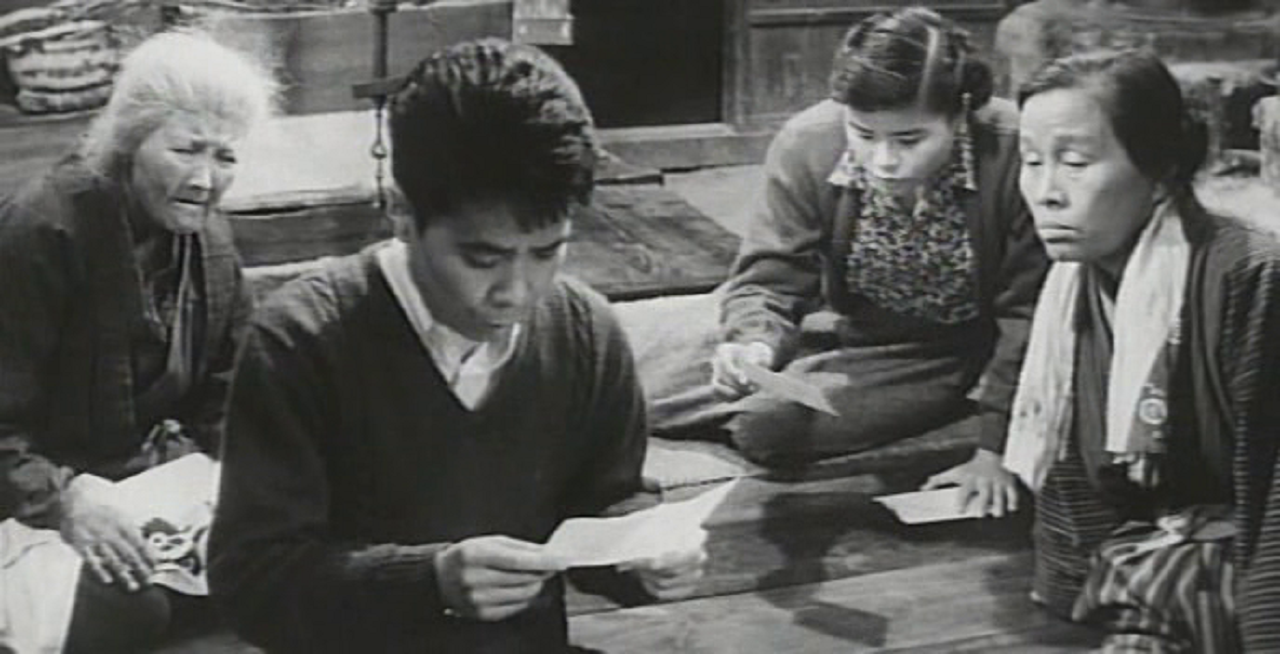

11 year old Kiku (Emiko Takahashi) and her younger brother Isamu (George Okunoyama) find themselves the object of curiosity and casual cruelty as their classmates taunt them with jibes of ‘Blackie’, ‘Gorilla’ and comments about bananas being their favourite food. Unknown to both their father was a black GI, now gone back to the US. With their Japanese mother dead and the pair raised on a farm by an elderly aunt (Tanie Kitabayashi) who can barely cope with the back-breaking work needed just to earn a pittance, a decision has to be made about Kiku and Isamu’s future in a society with little tolerance for outsiders.

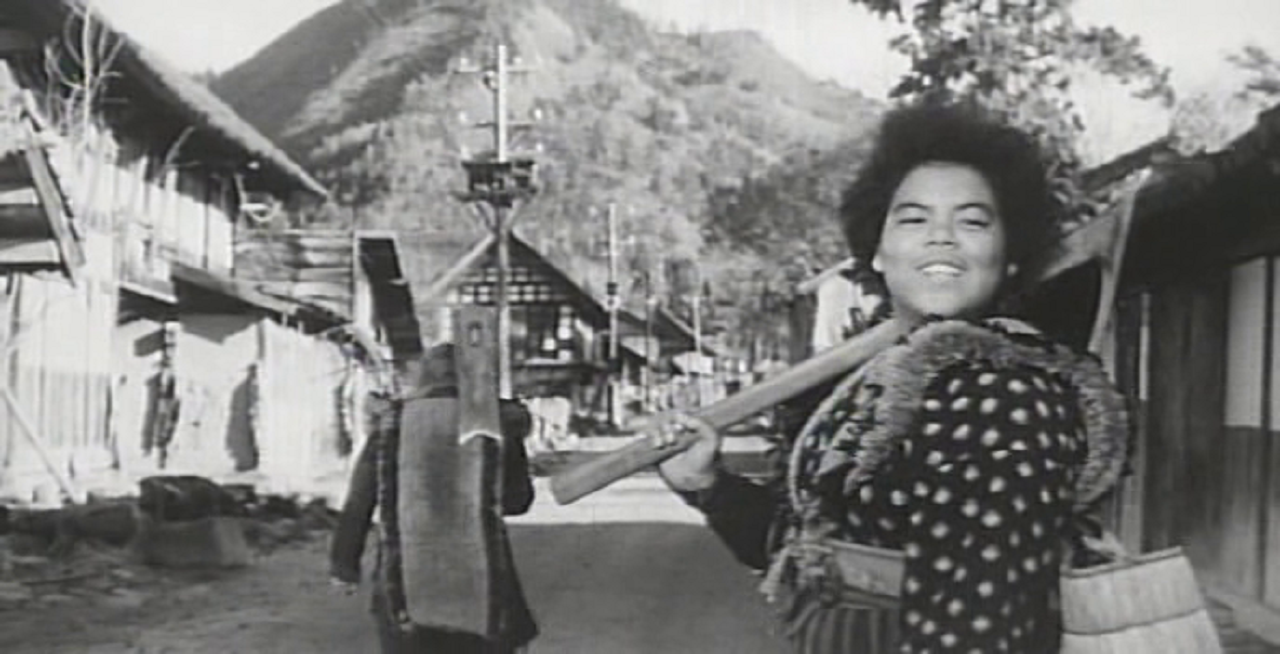

This movie gets me every time. The brilliance of Emiko Takahashi’s performance aside, I think the genius of it is that her character Kiku is a figure on the verge of adulthood, an 11 year old innocent with the body of an adult who doesn’t yet understand the impact of her skin colour in a society as racially homogenous as Japan. So your heart just aches at the hurt Kiku and her younger brother Isamu feel as they’re insulted by classmates and become the object of intense public curiosity whenever they venture into town from their small village. When Kiku delights in buying a hairgrip for herself from a street vendor, a pair of Japanese women look on in bemusement; “She wants to pretty herself” says one, as if talking about some imitation of a human being cooked up in Frankenstein’s laboratory. It’s very hurtful, especially since we can see that neither Kiku nor Isamu have a malicious bone in their body.

On the contrary, they’re a pair of perfectly ordinary kids who enjoy fooling around, going to school and helping Aunt Shige with her work on the farm and we quickly feel very protective toward them. Yoko Mizuki’s script has fun with the playground insults hurled at Kiku and Isamu. There’s a lovely scene in which Kiku’s sheer size means she can get revenge on her tormentors during a boys vs girls dodgeball match but the disapproval Kiku encounters outside of school from the general public is another matter altogether. That can’t be overcome by force and when Kiku gives Isamu a poke for misbehaving at a public festival the alarmed reaction from onlookers, “They’re more rough than Japanese kids”, says one, “Just think what they’ll be like when they’re adults” feels like ominous foreshadowing. As Aunt Shige and her neighbours – one of traditional outlook, the other younger and more liberal – acknowledge, the prejudice Kiku and Isamu face is only going to get worse as they grow to adulthood and so are their reactions to their tormentors. What to do then?

The pros and cons of the ensuing discussion between Aunt Shige, husband and wife neighbours Seijiro (Koji Kiyomura) and Kimie (Aiko Asahina), and middle-aged single mum Katsu (Teruko Kishi) are conveyed in an admirably even-handed manner. Kimie wants the children to go to the US so they’ll enjoy a better standard of living. After all, toiling from dusk ’til dawn on a farm is no life for anyone. That sounds reasonable enough until her husband points out that blacks face prejudice and lynching even in America, so there’s no guarantee they’d have a better life. Katsu argues that because Kiku and Isamu’s father was a black American the seeds are foreign and ought to be returned, a comment that leads Seijiro to scornfully declare “We’re not talking about pumpkins!” Only Seijiro recognises it’s the happiness of the children that counts not his wife’s visions of affluence in another land.

What makes these arguments – both pro and con – so forceful is that by this stage we’ve seen for ourselves how harsh conditions on the farm are so we understand the imperative to get them out of there. But we’ve also seen how devoted Kiku, Isamu and Aunt Shige are to each other. They’re a family and tearing them apart feels troubling despite the good intentions. The younger Isamu doesn’t understand the significance and thinks it’s all a great laugh. Only Kiku perceives the gravity of the situation. A scene in which Isamu’s adoption by an American family is reluctantly agreed too and Imai’s camera cuts away to Kiku, silently, protectively watching over her sleeping brother quietly drives home the wrongness of what’s been decided.

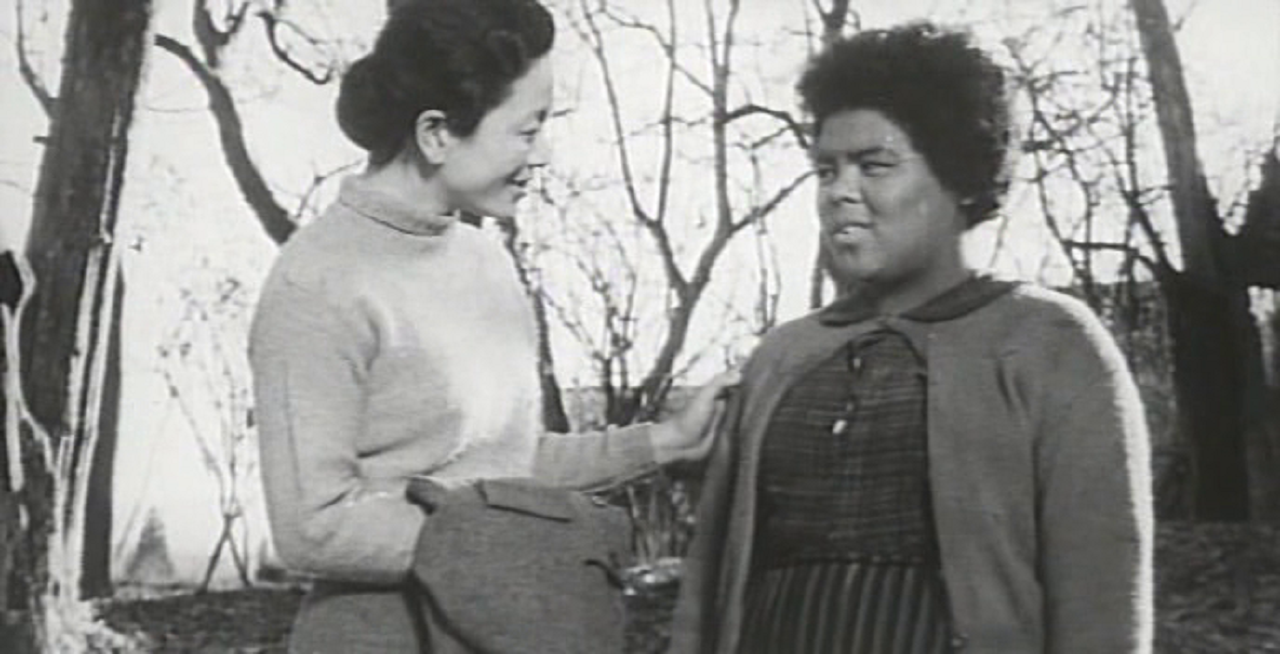

As much as Imai’s film is about the prejudice that outsiders face it also proves an unexpected rite of passage tale. Only a sympathetic teacher (Michiko Araki) seems to understand Kiku and in a beautifully played scene she puts Kiku’s anxieties about prejudice, her skin colour and her size (both of which harken back to a great line earlier in the film when she complains to her aunt that, ‘You told me if I ate lots of white rice I’d get paler. But all I did was get big!’) to rest. But when a couple of newspapermen force their way in and try to get a picture of Kiku for a freakshow article her aggression toward them convinces Aunt Shige that she must go into the local nunnery and this triggers an act of suicidal desperation from Kiku that’s so brilliantly handled by writer Yoko Mizuki and director Imai it actually finds light in its grimmest moment.

For underneath the snapped rope with which Kiku has tried and failed to hang herself there’s blood on her leg. “Did you hurt yourself?” asks Auntie before the truth hits her. It’s Kiku’s first period and as Shige explains the significance of this it gives Kiku the confidence to see herself not as a child but as an adult and therefore someone who simply no longer need be bothered by the taunts of her classmates, i.e., mere children. With Aunt Shige accepting Kiku as an adult it also means the girl can stay with her to work the farm, something we feel as delighted by as Kiku does. We’re under no illusions about the hard work ahead for both of them but this feels like absolutely the right decision. The final scene has Kiku cheerfully rejecting the insults of her classmates, “I’m too old to mess around with you like that anymore” she tells them. It’s a richly satisfying capper from a knockout humanist drama.

Imai is clearly sympathetic to his cast of poor and dispossessed characters yet his film never feels like its shoving a message down your throat. It’s all understated with the turbulent emotions effectively underlined by Masao Oki’s simple piano score. All the performances are strong here but the real star is Kiku herself, Emiko Takahashi. This girl gives such an open and guileless performance it really captures your heart and you find yourself getting very angry indeed at the insults and hostility she has to put up with. Thank goodness it all ends happily for her.

Hello

How can I view this film

I would

Like to watch it. I am half Japanese and black. I would also

Like to

Know

How can I contact the actor Emiko Takahashi thank you so much

Elaine, all I can suggest is that you get yourself a good search engine and look for Kiku and Isamu online. As for Emiko Takahashi this appears to be her one and only film credit (at least on IMDB). I honestly have no idea how you could contact her, where she is or even if she’s still with us (she’d certainly be well into her 70’s by now). I’m sorry I can’t be of more help but I wish you good luck with your search.

Elaine, it’s on YouTube, with English subtitles: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xqEIwlM4rhE

I know that the film hasn’t created English subtitles so far, and the DVD published is only with Japanese. I try to find any possibility of international release of the film in the near future. By the way, Ms. Takahashi might be still alive and doing a singer in Japan.