Last Updated on January 16, 2022 by rob

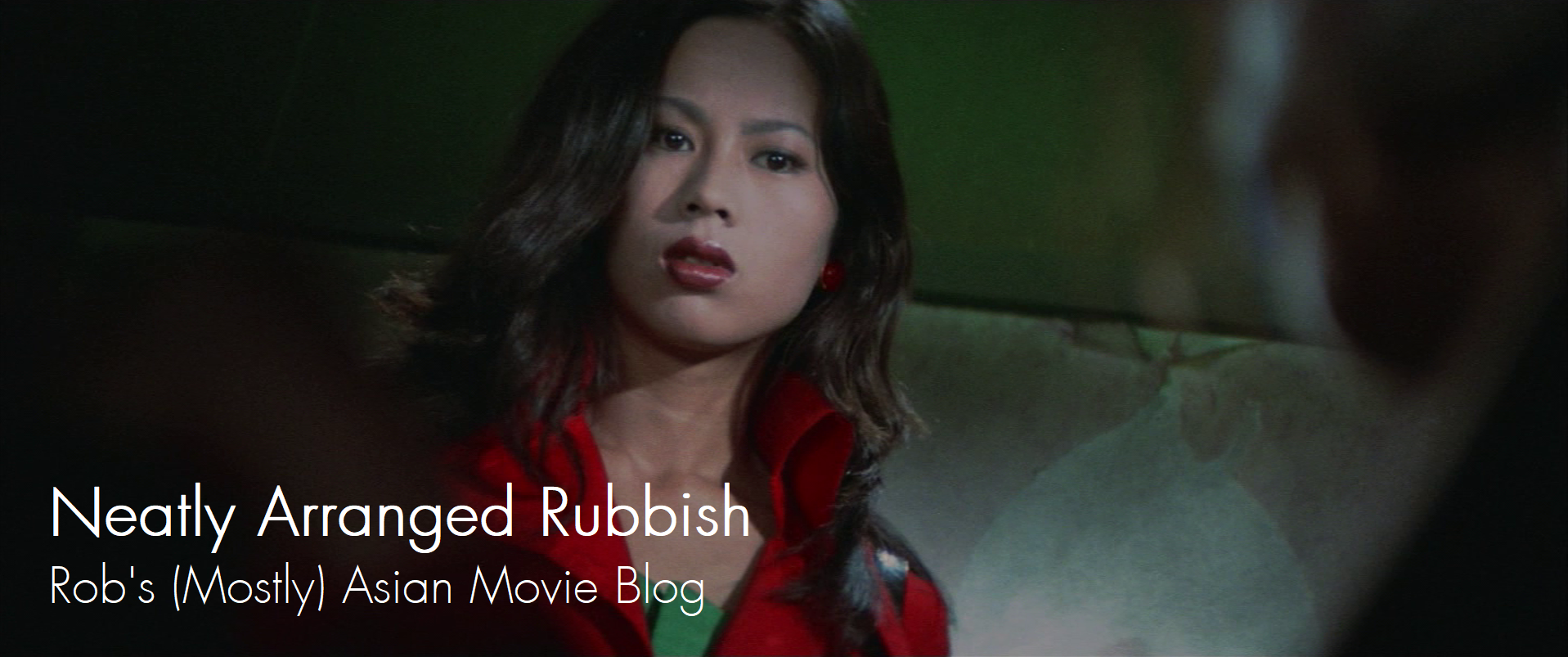

A wandering five man brass band that includes ladies man Torakichi (Hiroshi Ureko) and wannabe violinist Kokichi (Heihachiro Okawa) find themselves stuck at a seaside resort after their latest booking falls through. But the arrival in town of the travelling Asahi circus whose performers are out on strike at the circus manager’s tyrannical behaviour offers the men not just employment but the possibility of romance with the circus owner’s two comely daughters, Sumiko (Ryuko Umezono) and Chiyoko (Masako Tsutsumi).

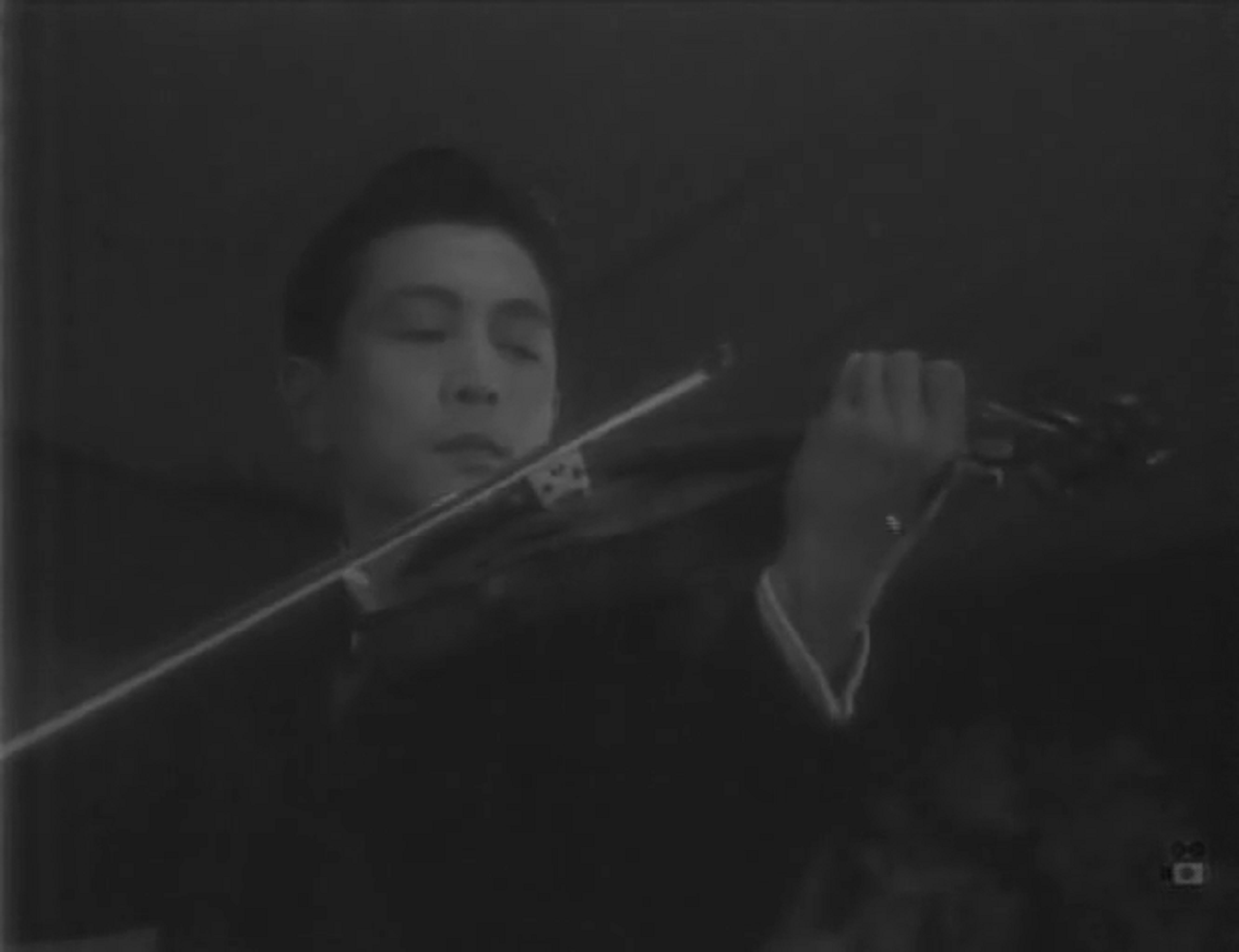

Naruse on good form here with a humorous tale of desperate musicians roped into being circus performers over the course of a couple of days. You can tell our band are in a bad way from the opening scene of them marching through town – one uses his cymbal as a fan, another struggles to hold his trousers up as he plays – and the less said about their awful music the better. The film quickly sketches in its characters. Prominent here are Kokichi, a trumpet player who dreams of being a famous violinist in Tokyo and drummer Torakichi. The latter’s a petty pilferer and ladies man pursued by a former girlfriend he literally jumps off a hotel lodging balcony to avoid. There’s a lot of good natured humour derived from these characters such as when Torakichi’s attempt to smuggle out a kimono under the nose of the landlady comes a cropper after one of his bandmates drops a beetle down his back!

And when Asahi’s ringmaster-circus-owner asks one of the musicians to perform on the circus trapeze, brushing off his concerns with, “And even if you fall,’ people would love that anyway!” you have to laugh at the guy’s incredulous reaction. And yet for all the humour there’s a wistfulness here, the quiet desperation of characters who feel their dreams are never going to come true. Come the big night Kokichi offers to play his violin for free to the circus audience but his dreams take a brutal knock as he’s booed off the stage. It’s a poignant moment when Chiyoko takes him aside and urges him not to give up. “The passion of a woman’s love” someone says when Torakichi finally accepts the woman who’s been following him and that absence in men’s lives is really the root of their unhappiness. They’re all affected by that. Whether it’s the circus owner’s cruelty which began after his wife left him or the band’s oldest member plunged into depression when confronted with memories of the baby daughter he abandoned after his wife died.

In fact so taken is this man by a 10 year old circus performer named Hanako and her tale of woe he gives her the money he earns from his circus performance as a clown (such a slyly appropriate touch!) only for Chiyoko to tell him that the child, “Lies to everybody like that all the time to get pocket money to buy sweets!” The film switches effortlessly in this manner between humour and drama and in so doing recognises in the sexes some eternal truths. The men may be untalented and gullible, the women bright and sharp, but by the same token the men possess a freedom the women don’t. Both Chiyoko and Sumiko are bound by a sense of familial duty – to their father horrible as he is, and – in a subtly played scene between the sisters where Sumiko expresses her puzzlement at Chiyoko’s reluctance to just up and run away with boyfriend Kunio – to each other.

This sense of loyalty and self-sacrifice resonates so strongly that even though the men are the nominal protagonists it’s the female characters we remember most. In fact both women get the strongest scenes. Sumiko’s forlorn declaration that she’s given up on her dreams could be taken as a challenge for Kokichi to prove her wrong except there’s too much weight, too much sadness, in her words to render it as anything other than a simple statement of fact. It’s a shame we learn nothing about the woman who pursues Torakichi, or Chiyoko’s boyfriend Kunio, the man leading the circus strike. Sumiko is a figure we’d love to know more of (when the two of them bid farewell to each other you’re left with the conviction that Kokichi will carry the memory of this woman with him for the rest of his days) but we’re left guessing at what brought her to this point. Perhaps it is better left that way. Naruse’s worldview of characters stuck with distant dreams and saddled with lives that have nothing to offer is leavened not just by the humour but by the director’s empathy for his characters. There’s no meanness here. He likes these people and we like them too.

As for the filmmaking technique there’s some very expressive editing juxtapositions and mise-en-scene on display. One in particular, a cut from the father raging at Sumiko over her disloyalty, to him firing a pistol at her really does make you wonder for a moment if he’s done the unthinkable… until Naruse’s camera pulls back to reveal we’re watching a stage act between father and daughter! I liked the scene in which Sumiko renews Kokichi’s faith in himself after his brutal rejection by the circus audience and the composition captures, cast on the tent behind them, the shadow of a woman with her hand held out in a gesture of promise. And an impressionistic moment in which Chiyoko’s POV on the swinging trapeze is superimposed over her face as she faints and falls is highly effective. Kudos also to an imaginative use of sound as the distant performance of Auld Lang Syne reduces Torakichi’s woman to tears after he eludes her. Finally, I must praise the wonderful footage of actual circus performers. There’s a guy here who lies on his back and delights the crowd by keeping a large barrel twirling and twisting in the air by using his feet. Old school that may be but I loved it!