Last Updated on September 29, 2020 by rob

In an era when executions are only carried out in autumn by royal decree Gang Pei (Ou Wei), a spoiled and only son, is sentenced to death for murder. With autumn a year away and horrified at the realisation that Pei’s death means her family will have no male heir his doting grandmother Liao (Bi Hui Fu) arranges to have loyal servant girl Chan (Li Tsiang) smuggled into the stockade so she can sleep with Gang Pei. That way, at least grandmother can be assured of an heir to carry on the family line. But an angry Gang Pei refuses to cooperate. With time running out, can he be persuaded to change his mind?

Despite its superficial resemblance to Shaw’s martial arts movies this Taiwanese gem is a work of unusual depth and substance. Its tale about the flowering of a brutish man’s better nature even as death bears down on him is told with such artistry that it has something of the quality of myth about it. Our protagonist Gang Pei quickly prove his own worst enemy – not only is he an arrogant bully whose loudmouth behaviour during his trial is so obnoxious it earns him a death sentence when a show of contrition might have got him off – but while in prison he rages with violence against everyone and everything. However the cleverness of Chang Yung-Hsiang’s script is the way that what at first seems like an exercise in ruthless pragmatism (who cares about Gang Pei, the family must have an heir!) is really about the redemption of this violent man.

There are hints of this early on. Grandmother Lia bemoans the fact that she’s the one who created this monster because she so spoilt Gang Pei as a child and we see flashbacks underline this. The gaoler Lao Tao (Ko Ting Hsiang) is forced to administer brutal beatings to subdue Gang Pei yet his eyes hint at a man clearly troubled by his actions. When he reveals to Pei that he too spoiled his own son and that the kid grew up a troublemaker until he was killed in a fight – “When I beat you, I thought I was beating him” he tells Pei – we understand why he’s agreed to help smuggle Chan into the prison despite knowing it’ll be the death penalty for him if he gets caught. So in a way the story’s also about adults trying to make amends for their failure as parents.

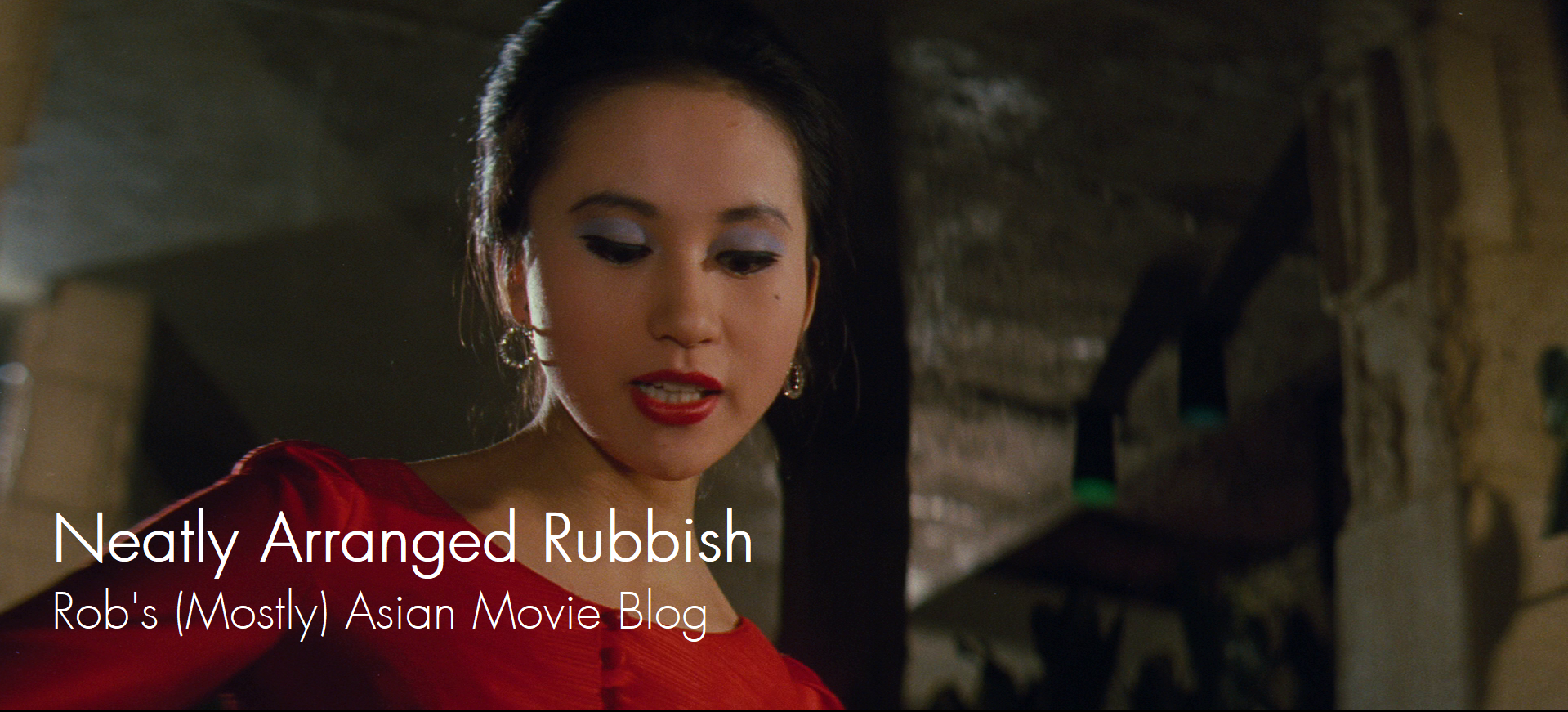

But as interesting and intriguing as that is it’s Li Tsiang’s sweet performance as servant girl Chan which gives the film its heart. Fate (because there is no other decent woman grandmother can call upon) and a sense of obligation since grandmother took her in as a child, ultimately persuade Chan to agree. But arriving at Pei’s cell in a bridal outfit in the middle of winter, her first meeting with him goes disastrously because the latter still believes he’ll be freed through the intervention of relatives. When the penny drops Pei reacts with understandable outrage at the prospect of having been written off as an animal suitable for no more than breeding. There are so many ways this scene could have been laughable – I mean, here’s a rough man in his cell with a pretty girl dressed in a bride’s outfit who’s come to shag him – but both actors are so good (Ou Wei really sells the idea of Gang Pei as a brute with a hint of conscience) they make every line, every gesture, every look, resonate.

The encounter ends on a bleak note but a second, in which Chan recognises the goodness underneath Pei’s rough exterior, is once again beautifully played and really socks over the attraction between these two with the subsequent change in Pei’s behaviour ingeniously shown not through action but inaction. It’s in Pei’s obedience to prison rules where once he’d fight against everything, it’s in his refusal to lash out at a warden who kicks him for dawdling. But it’s most strikingly embodied in the scene in which the gaoler comes to Pei the night before his execution, frees him of his shackles, opens the cell door wide and urges him to flee with Chan at his side. However Pei won’t go because he knows if he did it would be the gaoler’s death. It’s a deeply moving scene for what it says about both men and Ou Wei plays it with a quiet dignity.

Lee Hsing is not a filmmaker I’m familiar with (although on the strength of this I intend to correct that ASAP) and his direction here is excellent. His film has an overall melodramatic flavour but in practice it feels like a drama. He not only gets strong, involving performances from the small cast but really knows how to incorporate the large and evocatively designed studio sets (both interiors and exteriors) into the unfolding story in a way that renders them more than merely decorative. He achieves this by aligning the passing of the seasons with the changes in Gang Pei. Our protagonist is at his most unbearable in winter, begins to change in spring, matures in summer and faces his execution the following autumn with a dignity and courage inconceivable at the film’s start. It’s a simple conceit but it works really well because Hsing doesn’t overdo the comparison – it’s a few lines of dialogue at the beginning, the occasional cutaway – and it underlines the elemental nature of this story about a man who can’t tell the difference between right and wrong until someone’s love shows him the way.

Even Chan, the humble family servant, so grows in stature as a result of her time with Pei that she’s able to stand up to an avaricious cousin who wants to seize the family home for himself. The final scene of Gang Pei being escorted to his place of execution brings the story full circle (the film opens with an execution of pitiful, desperate wretches). The difference is that as Pei rides in the cart to his doom through a bleak, mist-shrouded forest he is neither angry nor afraid. As Chan and another family servant look on from the bushes they – and we – perceive not a monster but a man of honour and dignity. It’s a great climax and the final seconds as Gang Pei and his guards vanish from sight over the brow of a hill feels perfectly judged.