Last Updated on January 25, 2021 by rob

14th Century Japan; an ageing general named Moronao (Eitaro Ozawa) whiles away his time at a private court. When his courtesan Jijyu (Nobuko Otowa) unwisely hints at a Princess of rare beauty who lives in the area (Woman of the Dunes‘ Kyoko Kishida) the General instantly becomes smitten and begins sending the married woman love verses. The verses are politely returned but with each rejection Moronao’s determination that he shall have this woman – whom he has never met and doesn’t even know – grows stronger.

Another samurai drama then but of a particular type – what the Japanese refer to as ‘cruel historicals’ – films, like Inoue Umetsugu’s The Third Shadow and Tokuzo Tanaka’s The Betrayal, whose focus is not on heroic Generals or honourable samurai but on how bloody awful life was for those under them. Against a backdrop of crumbling power structures in which the country’s rulers and their servants have been forced to flee their palaces from invading barbarian hordes Shindo’s film begins as an ominous chamber piece and ends up as an intense, visceral horror movie in which most of its characters end up dead or mad. The horror here comes not from supernatural demons but from Moronao’s loathsome and all too human monster whose subjects must constantly satisfy his every whim (and in the process become as monstrous as he is) merely to survive.

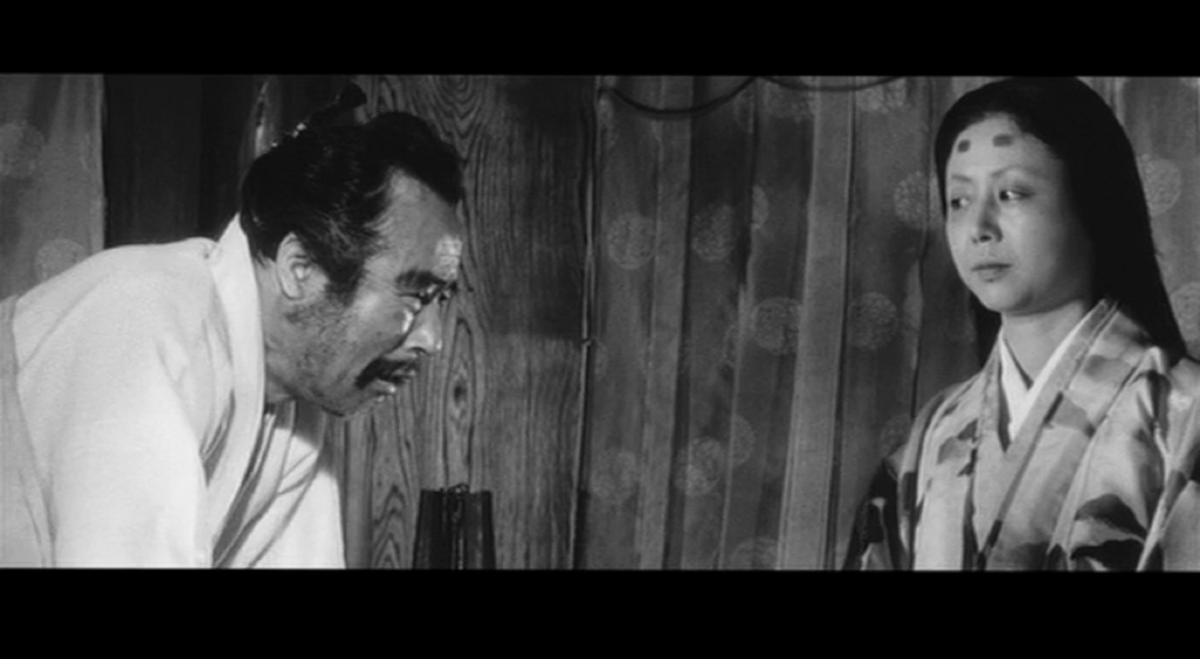

With the bulk of the movie essentially a two-hander between the General and his courtesan it’s Nobuko Otowa’s (in real life Mrs Kaneto Shindo) magnificent performance as Jijyu that dominates the movie. As both a sort of emotional barometer of the General’s mood at any given moment and the person responsible for carrying out his orders, Jijyu at first appears to be the real power (in a neat bit of misdirection Ozawa’s General is set up for us as a harmless old fool and an early visit to spy on the Princess as she takes a bath has a distinct comic edge) but part of the film’s power is the way it slowly reverses these initial impressions. Ultimately, Jijyu proves powerless to dissuade Moronao as he plots to isolate the Princess by ordering her husband and his men to depart for war. But when the Prince outwits Moranao by departing under cover of darkness and taking his wife with him an enraged Moronao orders a brigade to capture and execute the Prince and his men, instructing Jijyu that only the Princess is to be returned alive. Needless to say, things don’t go as planned.

Jijyu behaves quite despicably here and yet the character never loses our sympathy (even when she attempts to emotionally blackmail the Princess into accompanying her) because, unlike Moronao, she has a conscience. We can see she’s alarmed at what she’s being asked to do but she’s in an impossible position. Either Jijyu satisfies her boss or it’s her life. That self-awareness is a trait seized on by the Prince who, as Moronao’s brigade of samurai close in for the kill in the film’s climax, ominously instructs Kikyu that she will bear witness to what is about to happen. Although Otowa dominates the film there are fine performances from the rest of the cast with Kyoko Kishida particularly good as a woman from much the same background as Kikyu but unlike the latter one who refuses to succumb to her fate. Extremely well shot by Kiyoshi Kuroda and with an equally impressive score by Hikaru Hayashi (a scene where a demonically-lit Jijyu looks on uncomprehending as the Princess and her husband declare to each other their willingness to die rather than give in is a spellbinding example of each man’s skill), this is a superb film from Shindo featuring both his trademark theme about the resilience of the human animal and a climax that is truly the stuff of nightmares.