Last Updated on September 29, 2020 by rob

Bayinbulag (Ganghulag) and Somiya (Bayirtcya), two children from different families, grow up together under their adoptive Grandmother (Dalarsurong) in a Yurt on the Mongolian grasslands. At his Grandmother’s urging Bayinbulag agrees to marry Somiya but his education keeps him away from home for three years and when he returns it’s to discover that Somiya has become pregnant by the local lothario. Enraged, Bayinbulag walks out on his family but 12 years later returns to his village to find out what became of Somiya.

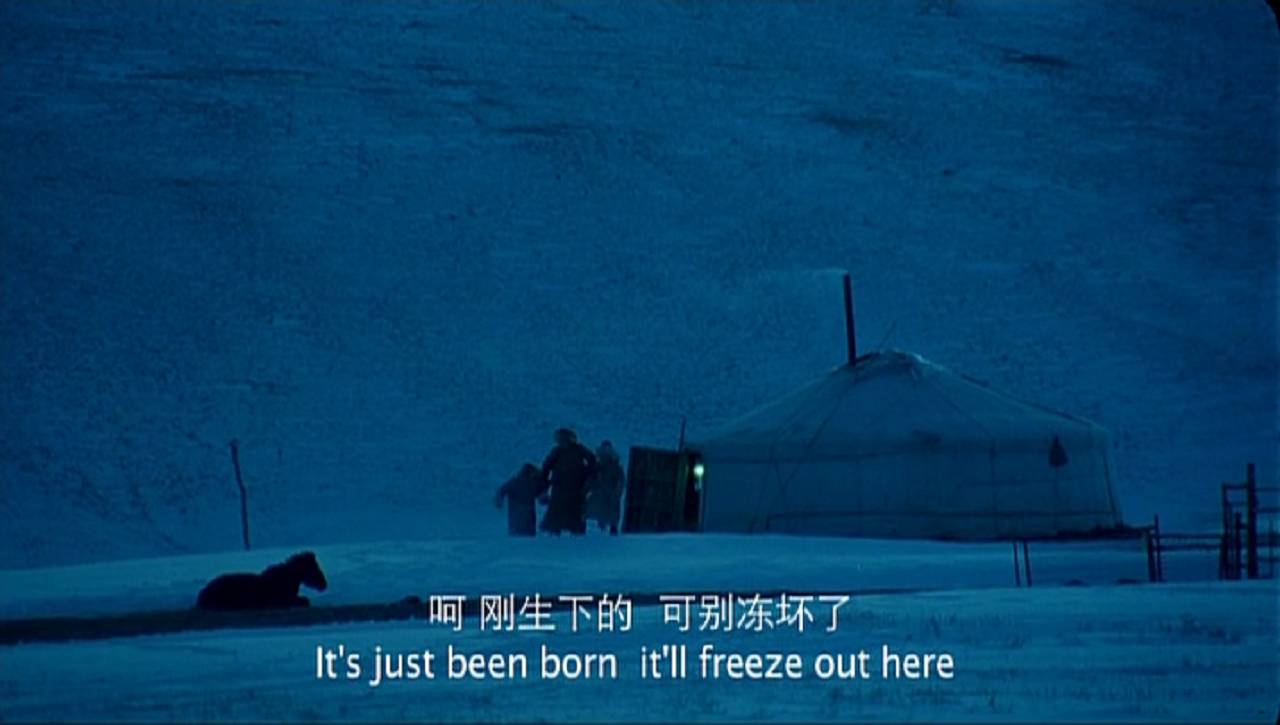

A strange and stirring tale which elides its spectacular Mongolian landscapes with three likeable and involving characters so skilfully that by the end we feel it’s not just a relationship that’s been severed but a connection with the natural order of things. Fei Xie’s direction evocatively captures the lifestyle of a nomadic people, circa late 1970’s/early 80’s, who herd sheep and horses for a living (the latter dependent – so we’re told – on their being a man in the family), who live in a Yurt (basically a big tent with its own front door) and who have to literally move their home from the uplands to the lowlands every autumn to avoid the winter snowfalls. Travel is mostly either by foot, horse or cart. It’s a physically demanding life to say the least but Bayinbulag and Somiya take to it like ducks to water and the engaging, naturalistic performances from the child actors pull you right in.

Bayinbulag’s destiny as a child of the grasslands is neatly linked with a new born foal that’s gotten lost and whom the children discover outside the door of their home one winter’s night. In time the boy learns to ride the horse – given the splendid monicker of Ganggang Hara – and the animal becomes as much a part of the family as the children. When Bayinbulag walks out on Somiya and Grandmother it’s Ganggang Hara who comes racing across the plains after its master as he rides off on the back of a truck – a great, stirring scene. And I liked the way the children’s budding sexual awareness is ever so gently hinted at in a visit to a temple as the children gaze, uncomprehending yet fascinated, at the erotic statue of a goddess. Despite that Xie’s film has a slight emotional distance from its characters. Much as we like the characters his film never lets us get too close to them. But once the third act rolls around, with the now 30-something Bayinbulag’s reunion with Somiya, the latter’s account of her life comes tumbling out and your heart just aches for the poor girl.

We learn that Somiya’s eldest daughter, the sweet Qiqig (Wendilya), is the bastard offspring of the man who seduced her 12 years before and as such the butt of insults from the rough, drunkard husband with whom Somiya’s subsequently had four other kids. In flashback we see how Grandmother went senile as she spent her days searching for Bayinbulag, in her confusion bringing in strays and drunks and pretty much anyone else who crossed her path. In another we see how Ganggang Hara died towing Grandmother’s body to its burial spot leaving Somiya stuck with the newly born Qiqig in the middle of a fierce snowstorm only to be rescued in the nick of time by her future husband. It all sounds as if Bayinbulag should be horsewhipped for his callousness but the film is fair in showing why Bayinbulag (who’s now a singer-musician) felt he had to leave and Somiya’s request to him that if he has a child he give it to her to raise implies that what’s been lost here is not simply a happy marriage but a way of life inextricably connected to the Mongolian grasslands.

It’s that awareness that makes the film poignant and mysterious and kind of rousing, really. The casting of Bayinbulag and Somiya at different stages of their lives never feels less than spot on and Renhua Na as the elder Somiya brings a touchingly forlorn quality to her performance without tipping over into melodrama. I especially appreciated the parting gift of a pen from Bayinbulag to Qiqig. It’s a moment that carries its own resonance because we learn early on that Somiya – because she’s a girl – was never sent to school and thus never learnt to read or write. And there’s a most poignant use of song by Bayinbulag – a response to the older Somiya’s litany of woes – in which the lyrics he gently sings embody the film’s theme. The movie is beautifully shot by cinematographer Jing Sheng Fu with its visual design of characters at work and play in the midst of vast landscapes subtly working on the viewer to persuade us that these two elements are inextricably linked. “We are Mongolia’s children,” sings Bayinbulag, “In love with the land of our birth.” All true and the sadness of this lovely film is that it’s about a man who forgets that and comes to realise too late how much it’s cost him.