Last Updated on October 6, 2020 by rob

A renegade scientist passes onto the Russians a doomsday virus developed by the US military. But the virus escapes and proves unstoppable. Hospitals overflow with dying patients and mass panic erupts. Overwhelmed, the authorities begin burning mounds of corpses in the streets while the US President (Glenn Ford) and a wily senator (Robert Vaughn) try to identify the source of the virus as a fanatical general (Henry Silva) demands a nuclear response. In Antarctica, where the extreme cold renders the inhabitants of scattered research bases immune to the virus, the survivors must begin again.

A wholly undeserved flop on its release Virus remains one of the most memorable entries in the end-of-the-world/post-apocalypse genre. With a large Japanese and American cast – besides Ford and Vaughn there’s George Kennedy as a naval captain, Olivia Hussey as a scientist and Chuck Connors as (don’t laugh) a British submarine captain – and location shooting in both the Antarctic, Japan and the US at a reported budget of 16 million dollars (a big sum for a Japanese movie) it’s an impressive looking production Virus opens with a British nuclear submarine surveying Tokyo and to the horror of the sub’s sole Japanese occupant Yoshizumi (Kusukari Masao), finding nothing but corpses (the true meaning of this on Yoshizumi will become apparent only much later).

The film then flashes back several years to show us how this nightmare came about and director Kinji Fukasaku (a reliable studio director who made his reputation with Yakuza movies but was versatile enough that he could turn his hand to pretty much any genre) depicts the unfolding chaos of the early scenes through a mixture of archive news footage and sharply dramatised scenes set in a Tokyo hospital in which the staff end up completely overwhelmed by the dying. Some of the news footage here is distressingly graphic but the overall effect is undeniable; you really do feel like you’re witnessing total societal collapse. Across the Pacific things aren’t any better in the US. The final scenes between Ford and Vaughn in the Oval Office, both of them wracked by the disease, are really moving. In a last call to scientists, diplomats and military staff who’ve survived in Antarctica the dying President begs them to ‘This time, try and work it out together.’

Virus’s first half essentially culminates in a disturbing scene in which a nurse from the Tokyo hospital – who appears to be the only plague survivor in the whole of Japan – understandably embraces suicide so she can be with her partner in death. In a poignant moment the film cuts to her husband, a scientist at an Antarctic research station, who seems to telepathically sense his wife’s desire and before anyone can stop him simply runs out into the cold to die so he can be with her. As melodramatic as that might sound (and it actually isn’t) it’s disturbingly persuasive. Why, after all, would anyone want to stay alive finding themselves in a hellish situation like that? It’s a mark of the film’s integrity that it doesn’t back off from what would be an all too plausible choice for some of those unfortunate enough to have survived the initial disaster.

Refocusing on the inhabitants of the Antarctic research stations the film quickly re-establishes a likeable protagonist in Kusakari Masao’s workaholic geologist Yoshizumi and sets up a poignant romantic attraction with Marit (Olivia Hussey), one that can’t be consummated because Yoshizumi is psychologically unable to accept the death of his wife and the accompanying guilt he feels over his couldn’t-care-less attitude to her pregnancy back in Japan (glimpsed in flashback). It’s only on reflection that one realises the emotional significance of that opening scene for Yoshizumi’s character in which he – on board the British sub – sees for himself the cobwebbed skeletons that litter the streets of Tokyo and the reality of his wife and child’s fate finally hits home.

The script by Kiji Takada, Fukasaku and Gregory Knapp and based on Sakyo Komatsu’s novel avoids getting bogged down in soap opera sub plots, preferring instead to examine the challenges presented by attitudes that now seem outdated. Members of a Norwegian base camp shoot each other dead over a pregnant woman whose future seems too bleak to contemplate. The woman, Marit (Olivia Hussey) and her child survive to be rescued by a Japanese expedition. But her arrival immediately raises another issue. With 800 men and just eight women traditional notions of a mate for life are no longer tenable and of necessity the breeding imperative is paramount.

In a sober and heartfelt speech one of the women acknowledges the reality of a situation in which they have to take the men as their lovers without discrimination but wonders whether it is even possible for them to overcome their natural instincts. When the film jumps ahead a year later there’s a charming party scene in which the women are sitting there with their new babies, the men all suitably attentive toward them (which makes perfect sense because if you think about it if nobody knows who the real fathers are then everybody can feel they have a stake in the future) and the prospects for the colony seem, if not assured, then at least a damn sight brighter than they did a year earlier.

With effective thumbnail sketches of the various nationalities – a sort of mini UN – that exist on the base there’s a particularly good moment early on when the inevitable, childish jostling about who’s in charge in the new world order are abruptly resolved when the virus stricken crew of a Russian sub threaten to make landfall. Their arrival will of course kill everyone. But when a British submarine also turns out to be in the area it’s the Russian representative who ultimately grants the Brit captain (Chuck Connors with an acceptable English accent) permission to ‘Do what you have to.’

The showdown between the two subs is excitingly staged but in that moment you can also sense the old ideological differences between the survivors melt away. Yet the old world casts a long shadow. The biggest challenge turns out to be the prospect of nuclear armageddon from automated American defence systems that will interpret the seismic shock of an upcoming earthquake as a Russian nuclear strike and retaliate unless a team can reach Washington DC and shut down the system that Henry Silva’s mad General activated before his death. It’s a fascinating notion. Humanity may have all but wiped itself out yet the survivors must continue to struggle not just with the new world but the poisonous legacy of the old.

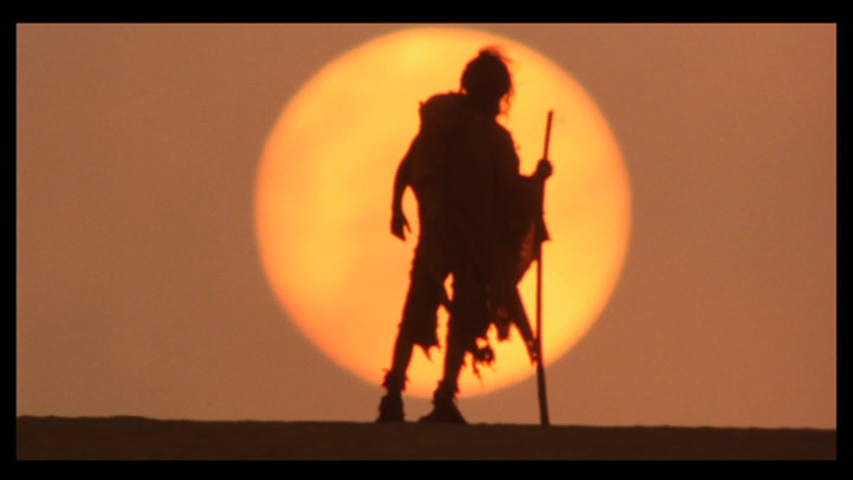

With the survivors having to flee the Antarctic colony because it’s been targeted by the Russians as a military installation, Yoshizumi and a US naval man journey by sub to Washington DC but the quake hits early and the nuclear strike is triggered. As Yoshizumi watches the monitors in the control room relaying images of nuclear silos across North America discharging their deadly cargo he calls the sub commander. In an echo of Glenn Ford’s last words he asks the crew to ‘Please remember .. we tried.’ If Virus were remade today the nuclear holocaust would no doubt be presented with all the digital sound and fury a visual effects house could muster … but you know what – I bet it wouldn’t be half as effective or memorable as those poignant words. In an evocative coda Yoshizumi stumbles through a post-nuclear wasteland to a striking encounter in a South American church where a surreal dialogue ensues with the skeletons of a mother and child who question the extent of Yoshizumi’s commitment to Marit and her baby.

Here, in a crucial moment that illustrates how he’s changed, Yoshizumi insists on his love for the pair and reunite with his beloved Marit and the (greatly reduced number of) survivors he ultimately does. ‘Life is beautiful’ he whispers through cracked lips. Yet far from sounding risible the words seem oddly appropriate for a film that exhibits a touching faith in the ability of human beings to survive no matter how bad things get. Are there any flaws in this epic? Sure, a couple of scenes tip over into melodrama, a few minor performances seem a bit OTT and there’s a painfully bland title ballad as a main theme. But this is all minor stuff and far outweighed by its strengths.