Last Updated on January 24, 2021 by rob

A bright teenager named Shuichi (Kazunari Ninomiya) lives with his mother and sister. But although outwardly happy the return of Shuichi’s estranged stepfather – whom he believes to have sexually abused his sister – stirs violent impulses in the boy. So Shuichi hatches an ingenious death-by-electrocution plan to murder his stepfather. But when a psychotic schoolmate gets wind of the murder Shuichi ends up blackmailed for money and when he resorts once more to murder events escalate out of control.

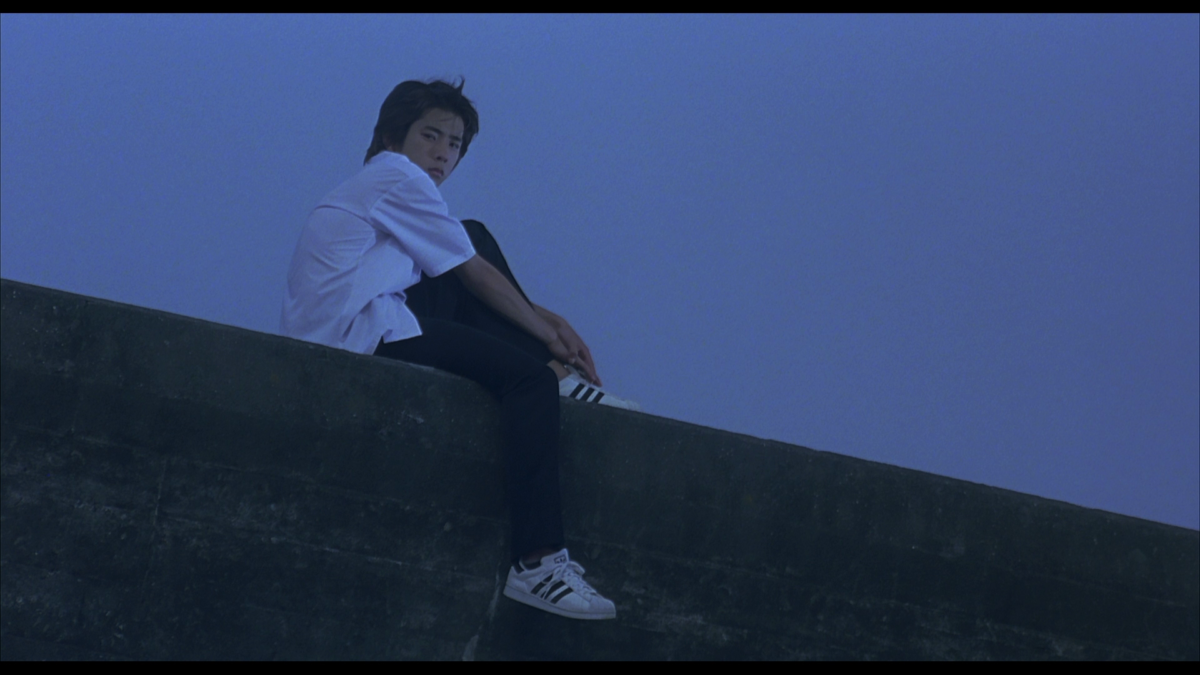

Anchored by an excellent naturalistic performance from pop star turned actor Ninomiya (‘Saigo’ in Clint’s Letters from Iwo Jima) this is a poignant lament for a wayward youth forced into desperate measures to protect his family only to see his actions blow up in his face. Determinedly non-judgemental as regards its murderous protagonist and enhanced by a hypnotically compelling Erik Satie-esque score from composer Hideki Tougi (along with bursts of Pink Floyd’s The Post-War Dream), it’s an absorbing portrait of a bright, eager to please kid rushing through life (a trait neatly symbolised by Shuichi’s beloved road racer bike on which he travels everywhere) but who has no control over the consequences of his actions. I liked the way the film subtly questions whether Shuichi is really motivated by altruism as he insists or, as one of his classmates suggests, an arrogant belief he’s superior to everyone else.

Ninomiya’s performance is spot on at selling this duality. That the film works effectively as both crime drama and character study is also thanks to the delicate touch of director Yukio Ninagawa. The early sequences touching on Shuichi’s childhood beatings at the hands of his stepfather are refreshingly restrained – almost to the point that you may wonder if Shuichi’s murderous plan isn’t an overreaction because it’s never entirely clear whether the stepfather really is a child abuser. Shuichi sure believes him to be but it’s also possible the man is no more than a drunken lout. The cause of a tense family standoff in which Shuichi threatens his stepfather with a baseball bat after his sister screams for help remains ambiguous. It’s an intriguing thought that if the sexual abuse angle really is all in Shuichi’s mind then we lose our sole reason for sympathising with his actions.

Director Ninagawa gets good performances from the cast and his film has potent visual metaphors ranging from the sight of the protagonist’s beloved road racer bike hanging in pieces from the ceiling of his garage – “It makes it look like the bike hanged itself” he observes – to his art teacher’s painting of a ferocious grizzly towering over a dead body, an all too apt symbol of the violent forces Shuichi himself will unleash. Forces which find their grimmest expression in a psychopathic classmate of Shuichi’s intent on murdering his parents because he finds their presence in his life an irritation. The film draws interesting parallels between Shuichi and the boy but leaves it up to the viewer to decide whether he’s any different from his psychotic classmate. I suppose beyond the crime/thriller elements here what impressed me most is that through it all our emotional connection with Shuichi never wavers.

He may be a killer, but he’s a killer for reasons we can empathise with. Even the veteran copper investigating the murder (an amiable performance from Baijaku Nakamura) turns out to be not entirely unsympathetic to Shuichi and when he shows an interest in his road racer his failure to ride the bike is not just comical but on a deeper level speaks to a fundamental difference in their respective natures not unlike that of the fable of The Tortoise and the Hare. Shuichi is fast but reckless, the cop slow but steady and as in the fable the hare’s arrogance and over-confidence prove his undoing. The hints here that Shuichi’s relationship with fellow classmate Noriko (Aya Matsuura) might have been his salvation (and once the game is up, Shuichi’s determination to finish things on his own terms) ultimately prove quite touching and lend the film the feeling of what amounts to an elegy for its doomed protagonist.