Last Updated on January 23, 2021 by rob

In 17th century Japan two Jesuit priests from Portugal Rodrigo and Garrpe (David Lampson and Don Kenny) attempt to spread the gospel but the country has turned against Christianity and both they and their Japanese converts face torture and death at the hands of Magistrate Inoue (Tetsuro Tanba) and his men, even as they search for their mentor Ferreira who arrived in the country 20 years before and then mysteriously vanished.

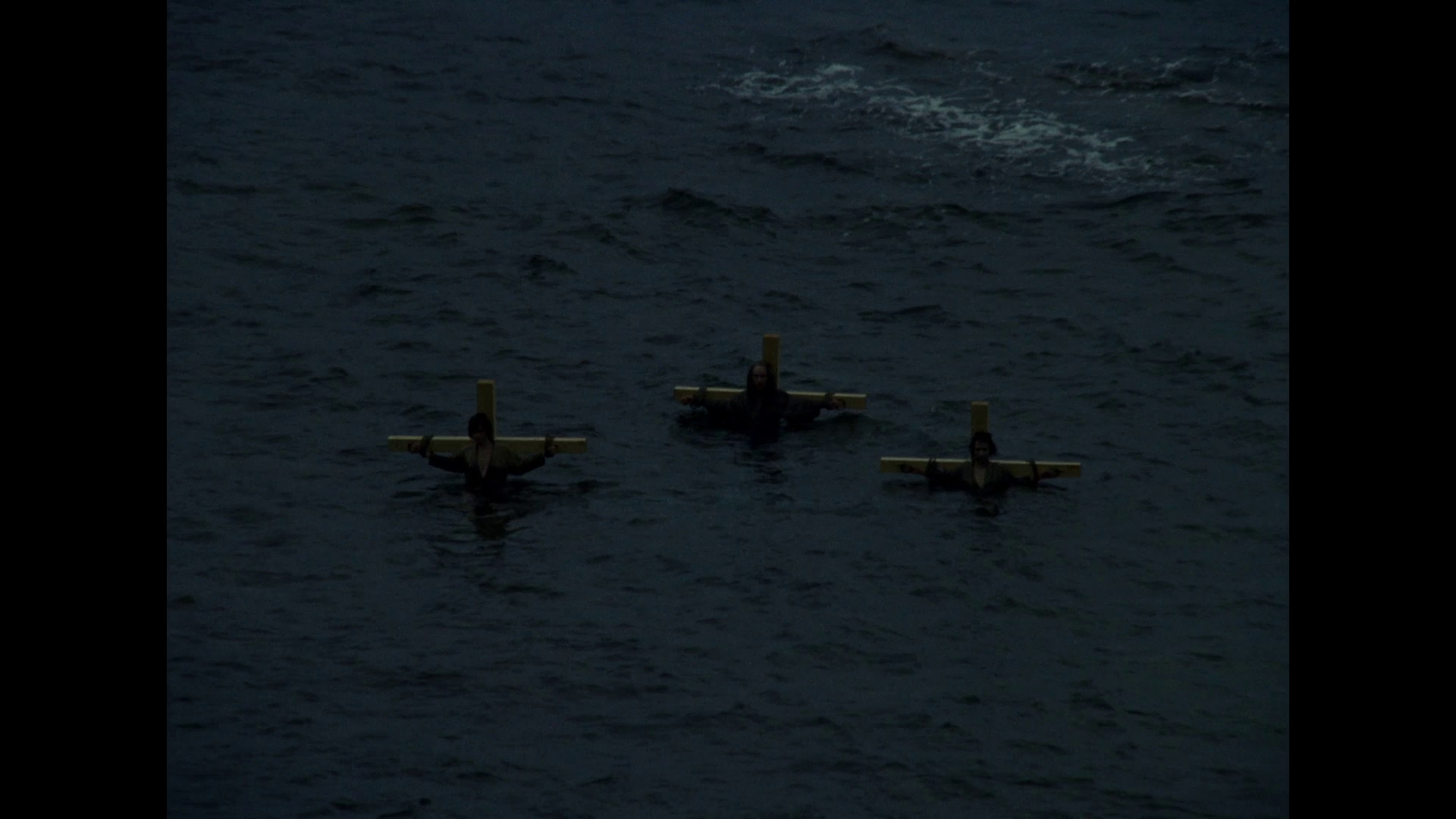

Silence was a very, very pleasant surprise. Anticipating a bloated theological slog (which I’m certain Scorsese’s unwelcome remake will be) Shinoda’s film is greatly aided by a structure in which the first half is given over to a taut hunter-hunted scenario as our two priests and their followers attempt to evade the authorities, and the second to their capture, imprisonment and torture as the faith of both Rodrigo and followers is gradually broken under interrogation by Magistrate Inoue (Tetsuro Tanba), whose ideological discussions with the priest prove every bit as destructive to Rodrigo’s beliefs as his sadistic torture techniques – in which the Christians have their neck cut and are then hung upside down over a pit to slowly bleed to death – do to their bodies. Indeed the most impressive aspect of the second half is a series of revelations, the most disquieting of which comes from the priests’ old mentor and concerns the nature of Japanese society and its notorious resistance to outside influences. Even when Japan does accept foreign influences – as this character devastatingly points out – it does so entirely on its own terms.

Featuring good performances from Lampson, from Shima Iwashita (Shinoda’s real-life wife) as a devout Christian and Tetsuro Tanba as Lampson’s interrogator, the film is just as impressive on the craft level. There’s another eerie, atonal score by Tôru Takemitsu and the stunningly impressive compositions by cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa (Rashomon, MacArthur’s Children). render a coastal village with its high cliffs and desolate beaches in such a way that at times it’s as if we’re on an alien planet. Miyagawa rarely misses an opportunity to frame the priests as the tiniest of figures in the landscape around them. With Takemitsu’s score it’s not only suitably disorientating but an effective foreshadowing of the surprises to come. One of the most adroit shots, again late on in the movie, is the sight of a wall filling the entire frame. As a metaphor for Japan’s seemingly hermetically sealed culture it couldn’t be more apt. This theological culture clash is further enhanced by Shinoda’s willingness to give both sides of the argument a fair hearing and there are times here where your sympathies won’t always be with the priests. Shinoda also leaves just enough room for us to wonder whether Lampson’s climactic repudiation of both his faith and his identity represents eternal damnation or a kind of liberation. This is an excellent film, thoughtful, touching and disturbing in equal measure.