Last Updated on September 28, 2020 by rob

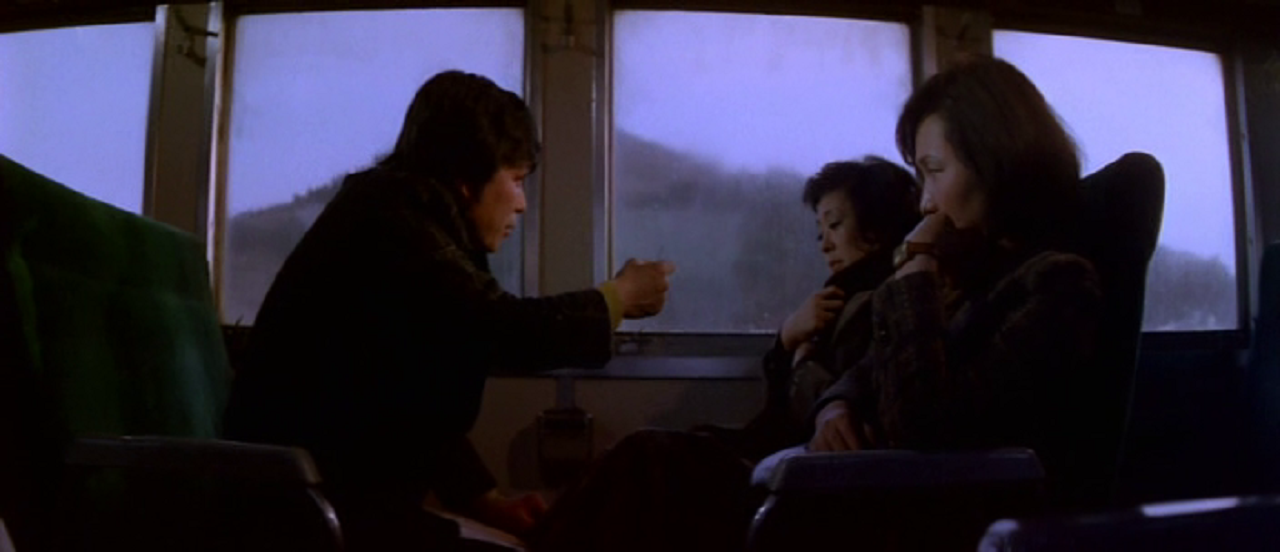

Middle-aged Sook-young (Kim Ji-mee) takes a train journey and recalls her abuse at the hands of men whose brutal treatment provoked her into killing in self-defence. A spell in prison leaves her suicidal but a temporary release under the watchful eye of a female warden leads to an encounter with Hoon (Lee Jeong-il) whose friendly persistence breaks through Sook-young’s mistrust and awakens in her the possibility of a new life. What she doesn’t know is that Hoon’s involvement in a murder means the police are on his trail and their time together may be much shorter than either realises.

This startlingly vivid portrait of a sexually abused woman turned murderer and now suicidal prisoner Sook-young (Kim Ji-mee), out on temporary parole and the young man named Hoon (Lee Jeong-il) who shows her how to live again is utterly compelling. Blunt statements from unsympathetic males about a woman’s place (‘The role of a woman is the rearing of babies, otherwise she has no meaning!’ being a typical example) collide head on with lurid colour schemes, canted camera angles, flashbacks and a pounding, propulsive disco/jazz score evoking a lurid fever dream feel in which our heroine struggles with the eternal question of why men desire so strongly to possess women’s bodies only to throw them away like trash when they’re done. Kim Ji-mee is excellent as Sook-young. Her performance increasing in power the more we learn about her character.

As she initially suffers one indignity after another we certainly feel sorry for her but when we catch up with her as a convicted middle-aged murderess – broken in both mind and spirit, little more than a mute shell of a woman – our heart positively aches for the poor girl. Lee Jeong-il is convincing as the decent young man who takes a shine to her. The pair have good chemistry and an unexpected subplot in which we see him accidentally caught up in a murder for which, though innocent, he’s going to take the rap, raises the stakes dramatically. Also good is the actress playing Sook-young’s warden. It’s a complete surprise that she turns out to be so sympathetic to her prisoner’s plight. The patient way she feeds Sook-young candy, like you’d feed to a child as a reward for good behaviour, says far more about the way life has been unfairly torn away from Sook-young, than any amount of dialogue.

As the story unfolds the warden escorting Sook-young is so sympathetic to her plight that she actually takes Hoon aside and urges him to make love to Sook-young and marry her before they arrive back at the prison. If that sounds unlikely then get a load of this; when detectives hunting Hoon for the murder of a taxi driver turn up on the train the warden easily persuades the cops into delaying their arrest to the point the pair are allowed to leave the train and find an abandoned carriage where they can make love! In lesser hands this sort of melodramatic plotting would seem utterly risible but director Kim Ki-young keeps such a tight focus on Sook-young that we become wholly absorbed in what is essentially a primal struggle to save this woman’s soul.

The end result is a gripping, highly stylised melodrama in which sex is viewed as both a punishment inflicted by men on women and yet, paradoxically, also their liberation from a cruel and unfair society. Despite ragged production values (struggling under a harsh military dictatorship, the 1970’s was the nadir of postwar South Korean cinema) and despite being the second remake of Kim Ji-hyeon’s original story – the first was Japanese director Koichi Saito’s impressive The Rendezvous (1972), this 1975 version is as different from that as can be yet an equally terrific film in its own right from one of South Korea’s greatest filmmakers.