Last Updated on September 29, 2020 by rob

In 18th century Japan honourable samurai Heizaburo’s (Bando Tsumasaburo) attempts to do the right thing are persistently misunderstood and he ends up arrested. Losing the love of the two women in his life, Namie (Utako Tamaki) and waitress Ochio (Shizuko Mori) and shunned by the townspeople for an undeserved reputation as a criminal Heizaburo’s good nature is further exploited by thief Kokichi (Nakamura Kichimatsu). Rescued by local Lord Akagi Jirozi (Nakamura Kichimatsu) it looks as though Heizaburo has found a saviour. But while outwardly respectable Lord Jirozi turns out to be a gambler and abductor of women and when his latest victims are Namie and her sick husband Heizaburo is forced to take deadly action to save them.

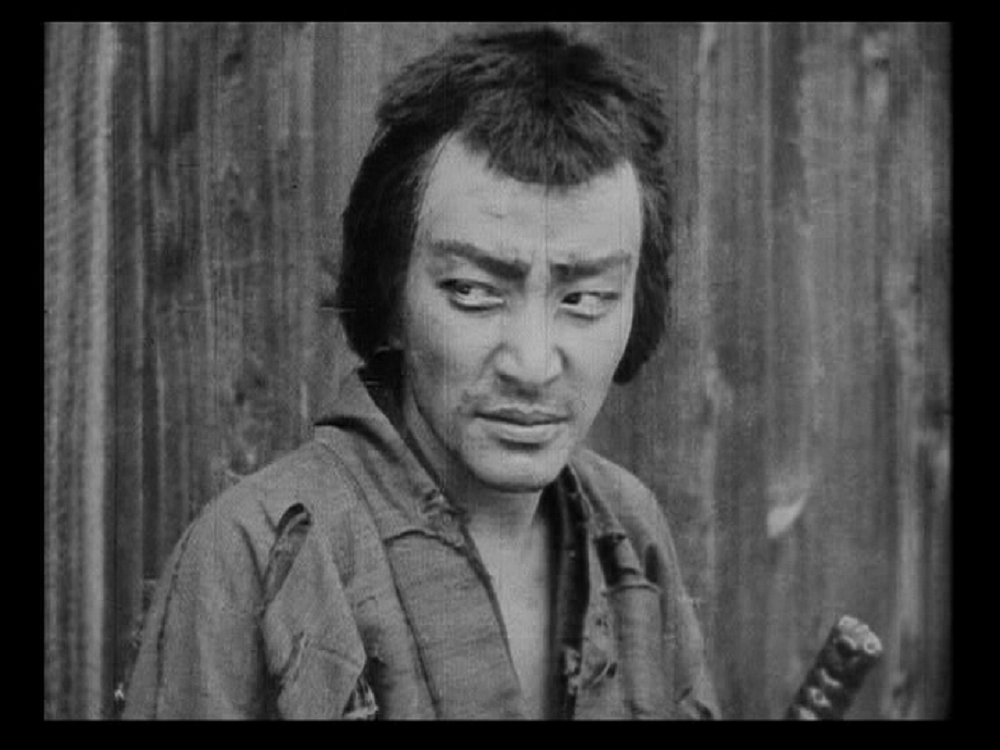

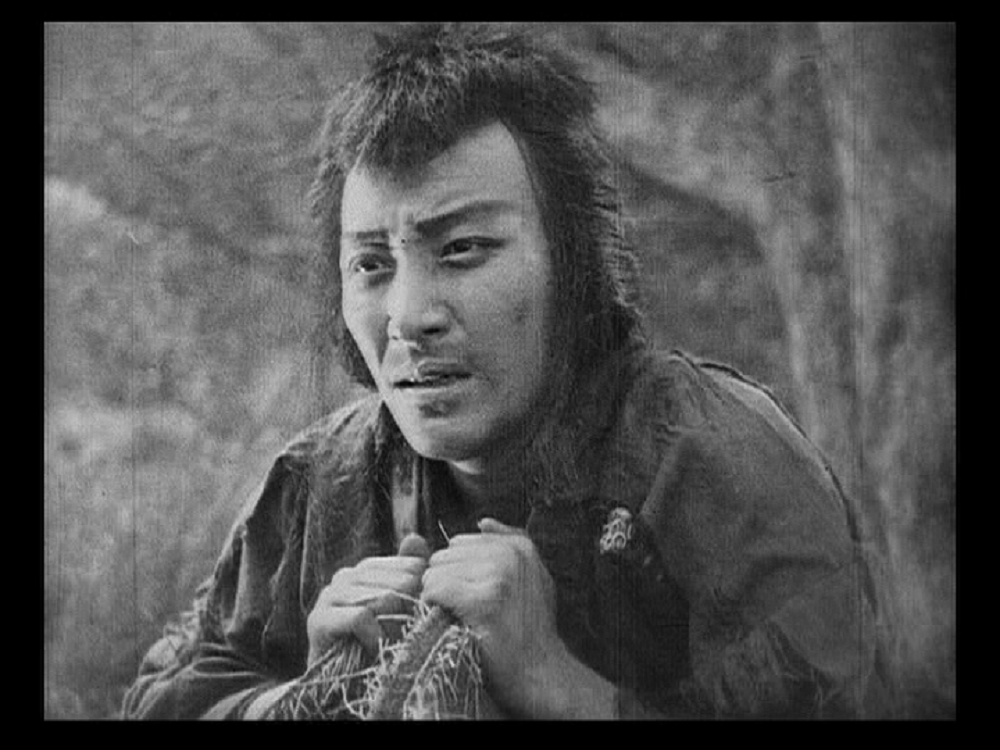

A splendidly heartfelt yarn about a misunderstood soul and dominated by a stirring performance from silent movie star Bando Tsumasaburo. I found it all quite moving and the final scenes pack a real punch. The star’s performance feels fresh and not much beholden to creaky traditions of melodrama. In fact there’s a clear awareness here of how to act for the camera and in scenes such as Bando’s contempt for the townsfolk who mock him for his ragged appearance, or his effort to befriend children playing in the street who flee from his presence, Bando most effectively underplays his character’s reactions. We’re sympathetic to this guy right from the start. Heizaburo does nothing wrong but once he gains a reputation as a bad ‘un every run in with the authorities means they assume the worst. The character becomes in effect a kind of anti-hero and must have been one of the earliest screen versions of that type.

Rokuhei Susukita’s script with its laser like focus on Heizaburo’s inner torment – so touchingly portrayed by Tsuasaburo, “Is there no one who can see my heart?” he cries at one point – means we wince every time the chain of calamities story structure knocks our hero back another step. One of the best moments has Heizaburo’s soul tested to its utmost when Kokichi abducts Ochio and brings her to Heizaburo’s room so he can have his way with her. It’s a strikingly staged scene with an expressionistic flourish as Ochio cowers in a corner and Heizaburo’s face comes right up to the camera in huge close up as his animalistic side tries to persuade him to rape the terrified woman. Of course Heizaburo doesn’t give in (although for a few moments it sure looks like he might) but along with another scene in which our hero loses his rag after a fellow samurai tips sake over his head the scene is important because it depicts Heizaburo as a man and not a saint. If Heizaburo was the latter the film would be far too one note to retain our interest. It’s this increasing resentment inside Heizaburo, our unease that society’s unjust treatment might push him to lose his self-control, that builds to a spectacular climax.

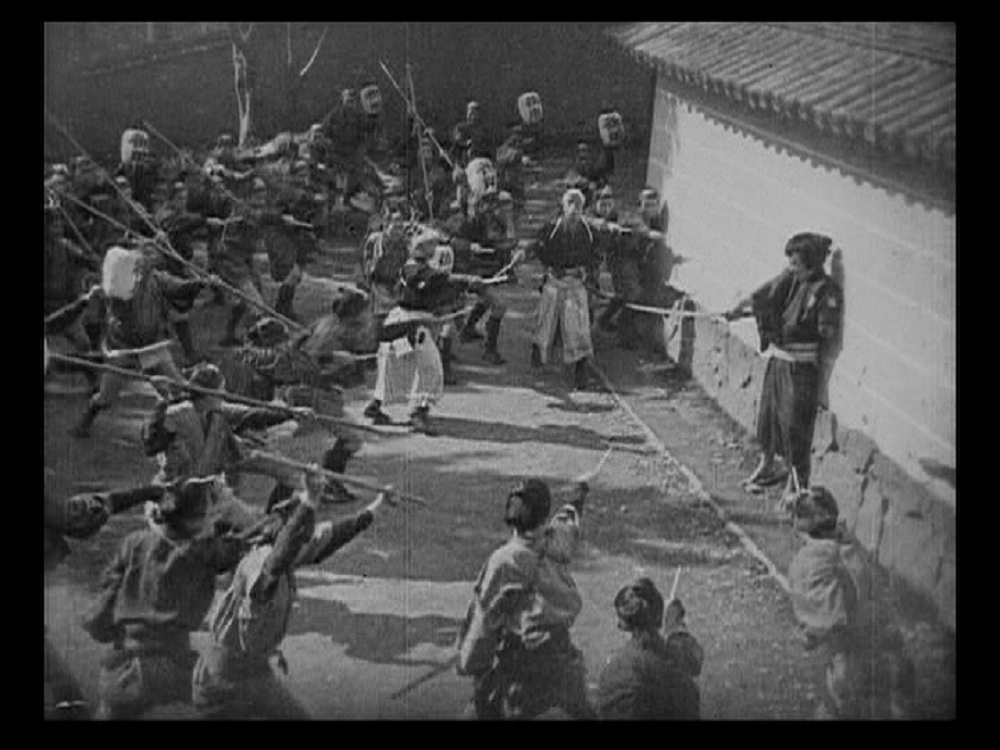

After killing Jirozi and his men for trying to rape Namie our hero once again finds himself blamed by the police and the locals. The result is a massive street battle as a desperate Heizaburo – now clearly at the end of his rope – fights off wave after wave of attacking police with lethal force. The sequence avoids any of the theatrical flourishes that sometimes dogged silent movies (when someone is slashed here they simply fall down) and director Buntaro Futagara stages the climactic battle as a series of long shots using lengthy single takes. A mobile tracking shot that follows Heizaburo’s fight as it progresses down the street stretches on for the best part of 2 minutes. The shot is broken up by a couple of quick reaction shots but it’s still an extraordinarily ambitious achievement. The influence of the Hollywood model is quite apparent on Orochi.

The story is well structured, thematically coherent and the cinematic technique on display is quite sophisticated. The long takes aside there’s a moment at the end of the final battle when Heizaburo comes out of his warlike fugue and sees all these people surrounding him, something the director conveys in a blizzard of fast – almost impressionistic – shots of individual faces all cut together. Comparing this with the 1966 remake what’s noticeable is how each film successfully pursues different emphases while juggling similar story elements. The suffering of our hero cuts deeper in the original but on the other hand the samurai’s love for the woman in his life and their mutual misery at being separated is more strongly put across in the remake.

The themes are different too. The hypocritical code of the samurai honour system is the target in the remake but the silent version is about the way society as a whole leaps to judgment about a person based on their appearance. Both films explore the difference between one’s public and private image with the silent version extending a redemptive touch in recognition of its hero’s true nature that the bleaker remake avoids. One of the key scenes in both films is when – during the final battle – the samurai’s hand is gripping his sword so tightly he can’t free it except by prising the hand off it, one rigid finger at a time. In Tokuza’s remake this image makes for a thrilling moment of high-stakes tension in the midst of an epic battle, but in the original it’s a symbol of how murderous rage has clouded Heizaburo’s judgement and the sudden shock of realisation for the samurai that he’s taken human life.

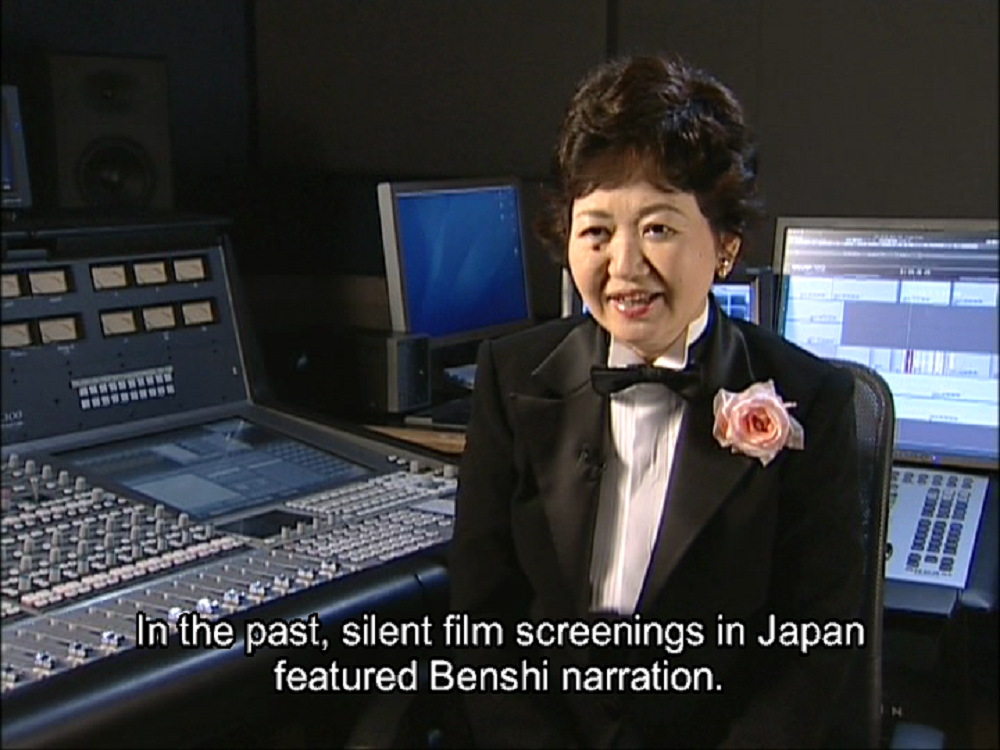

Unlike the bleak ending of the remake Orochi concludes on a movingly lyrical note as Namie and her husband – the only witnesses to Heizaburo’s selfless nature – kneel and pray for his soul as he, unaware of their presence, is marched by them (presumably we can infer) to his execution. That gesture might sound like cold comfort but so persuasively does the film immerse us in Heizaburo’s torment that the sight of these two really does pack a cathartic wallop. For me the film also brought a new appreciation for the art of the benshi. These were the narrators of Japanese silent cinema who gave live commentary and would supply the voices to all the characters for the benefit of the cinema audience.

For Western viewers this undoubtedly sounds odd but watching Orochi alongside Midori Sawato’s excellent benshi narration on Digital Meme’s DVD I came away seriously impressed. Not only did it enhance the experience but looking at the movie and the way it’s dominated by a character who suffers prejudice and misunderstanding from all corners it makes me wonder if Orochi might have been conceived as a specific vehicle for a celebrity benshi performer of the period. At any rate, an excellent film. Read more about the benshi here.