Last Updated on November 14, 2020 by rob

A street thug named Okita (Bunta Sugawara) emerges from prison after a five year stretch and hooks up with his former gang. Finding his old turf divided between two rival crime syndicates headed by Takigawa (Takeo Chii) and Yato (Noboru Ando) he begins muscling in on the former’s territory. But Okita can’t stay out of trouble and his love/hate relationship with Kimiyo (Mayumi Nagasi), plus his insubordinate attitude to gang boss Saiei, mean Okita’s days are numbered even as Yato tries to keep him alive.

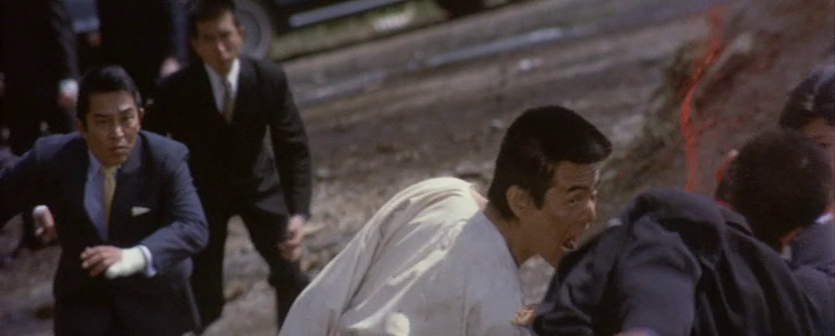

Watching one of Fukasaku’s gangster films is invariably like being gripped by the throat for 90 minutes. Even when the script is nothing special such is the lurid fever dream force of his direction you feel compelled to watch right to the last frame. Outlaw Killer is, nominally at least, a little different to the director’s better known The Yakuza Papers series in that the focus is not on the leaders or the footsoldiers of the Yakuza but on a born to lose street gang looking to make money anyway they can. Okita is a character completely unconstrained by Yakuza notions of loyalty, honour or belonging. His twin interests are fighting and fucking and his philosophy of life – such as it is – is summed up in a line he uses several times in the film, “Once a dog learns the taste of defeat, it never bites again.” He’s very much a force of nature then but Bunta Suguwara’s performance somehow makes this scumbag not entirely unsympathetic even though we witness him do the most appalling things.

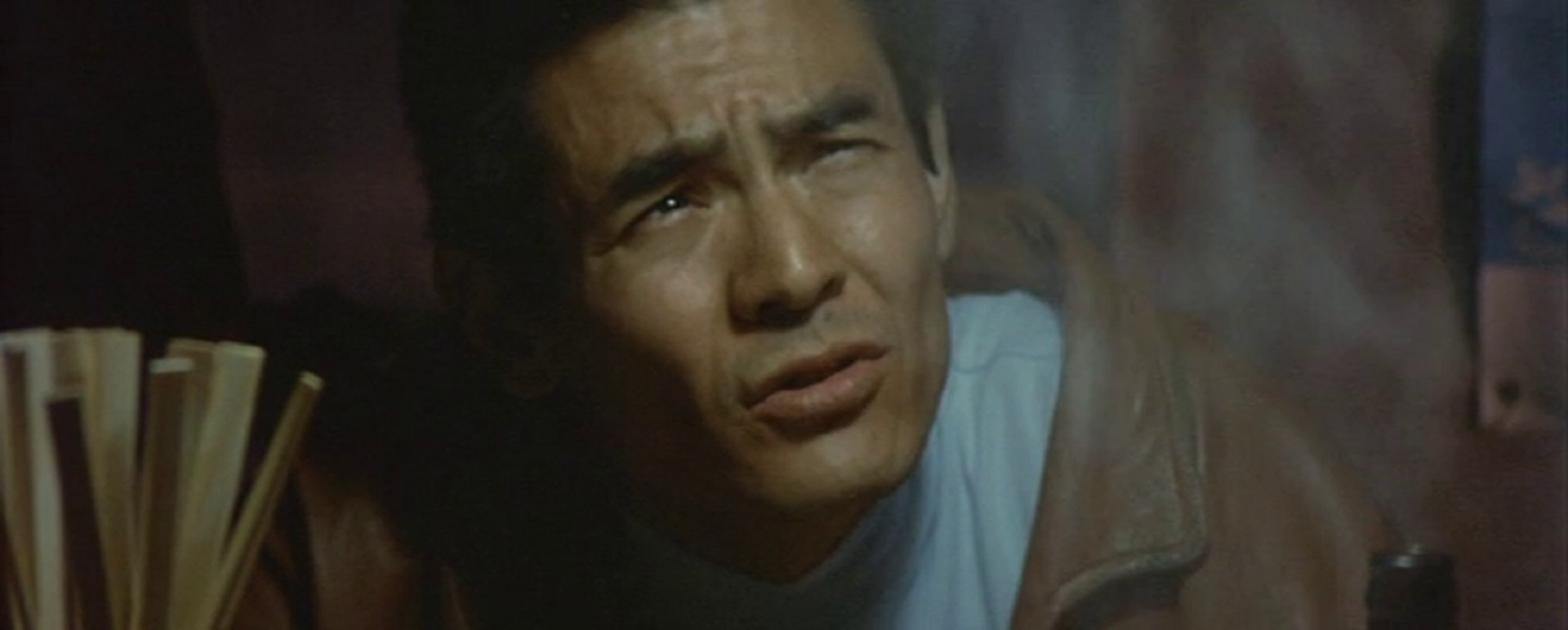

But Okita at least isn’t evil or sadistic. He does what he does because he simply doesn’t know any different and when confronted with the consequences of his actions – such as his post-prison meeting with Kimiyo who’s turned to prostitution to support herself after Okita raped her – you can see on his face flashes of guilt and remorse. It’s not much but this and a few other moments that genuinely shake him are just enough to keep us onside with the character and Kimiyo, whose intense love/hate relationship with the man who took her cherry and wrecked her life embodies the film’s fatalistic outlook, is an effectively unpredictable presence in Okita’s life. It helps the drama that Fukasaku doesn’t seem to be under any illusions about Okita or the thug life. All Okita can do is lash out at whatever’s in front of him. The possibility of him manoeuvring up the Yakuza chain of command never seems even remotely possible and his men follow him blindly to their deaths.

When Kizaki (Asao Koike), the one member of his group with brains, tries to fly out of the city it’s already too late. Okita has stirred things up to such an extent that the enemy are guarding the airport and Kizaki is struck and killed by a car while fleeing. Even Yato’s admiration of Okita because he reminds him of his younger self is given an astringent twist when Yato asks one of his men if they were really as bad as Okita. “No”, comes the response, “We were much worse”. The script by Fukasaku and Yoshihiro Ishimatsu is easy to follow and there’s plenty of street action here as Okita and his men alternately chase and beat up – and are then chased and beaten up by – Takigawa’s men. But the most poignant scenes are when Okita encounters a former cellmate whose wife has taken him back into her life even though the reason he went to prison in the first place was for slashing her face in a jealous rage.

They’re poor and living in a hovel but this man has enough empathy to recognise the sacrifice of this woman whose love has straightened him out and the debt he owes her. In that moment of acknowledgement, as the wife looks silently on, one senses the unlikelihood of such redemption for Okita even though we hope for the best in the scenes between him and Kimiyo. If it’s a bit disappointing that the involvement of Yata and Kimiyo in Okita’s life promises more than is ultimately delivered then Fukusaku nontheless socks over the melodramatic cliches of the film’s climax – as Okita’s gang are bloodily dispatched one by one – with verve. Indeed, that distinctive style of Fukasaku’s, in which the rapes, footchases, beatings and stabbings are depicted in an imitation of newsreel footage (as if the filmmakers had turned a camera on in haste to capture a mass brawl erupting around them) collide head on with stylised techniques like freeze frames, melodramatic musical stings, canted/overhead camera angles and voiceovers really evokes a wild, feral vibe that no other gangster movie has quite equalled.

This was the sixth and final instalment of the Modern Yakuza series (as the title suggests, the attempt was to update the Yakuza for a more modern audience), the first to be directed by Fukasaku and the first pairing of star and director. Even if one could have wished for a bit more from the script so much of this works so well that you sense the possibilities were the director to be handed a really good script. That, of course, would come with the following year’s The Yakuza Papers and its sequels. And just as an aside, it’s impossible to watch something like this and not feel that Martin Scorsese must have been influenced by Fukusaku’s early 70’s films when he came to make his own gangster movies. The style and themes are too similar to be dismissed as coincidence.