Last Updated on January 18, 2022 by rob

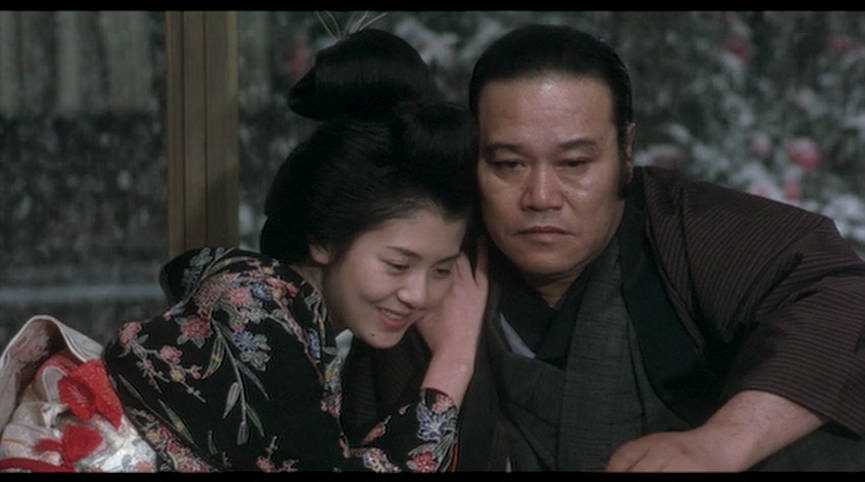

Japan, 1932; Brothel bodyguard Tomita (Toshiyuki Nishida) takes the innocent Botan (Yoko Minamino) under his wing when the girl is sold into the business. She quickly becomes the star attraction but falls deeply in love with Tomita while he only has eyes for his estranged wife Kiwa. But when a good-hearted Yakuza goon named Nioyama (Masahiro Takashima) falls for Botan, his ruthless boss Tamura (Nagare Hagiwara) plots her demise after she’s adopted by a rival politician running for election.

A terrific romantic melodrama from director Furuhata with a strong story, compelling characters, unexpected plot twists and boasting a thrilling, blood-soaked swordfight for a climax. As you’d expect from a superior director like Furuhata, everyone here, good guy and bad guy, star or bit player alike, is granted little character quirks to distinguish themselves (I particularly liked the two brothel madams whose money grabbing nature we’re warned about before we see it for ourselves in a quite hilarious scene). With his sheer bulk lead actor Toshiyuki Nishida makes an immensely likeable lead as Tomita because his size makes such a contrast with his polite and softly-spoken demeanour. He’s a bit like William Munny’s character in Unforgiven. A former wild man who has reformed his ways and who goes through the film quite willing to turn the other cheek and submit in the face of provocations until the bad guys finally go a step too far at which point Tomita grabs his old sword and transforms into a one man slaughterhouse.

That said, this isn’t an action pic but a poignant love triangle drama as the headstrong Yakuza Nioyama mistakenly perceives Tomita as his rival in love for Botan’s heart. There’s a nice line of humour too as Nioyama tries to win Botan’s affections by first showing off his muscles to her and then when that fails trying to woo her with the gift of a chest of drawers! That’s never going to compare with Tomita’s modest but worth-their-weight-in-gold kindnesses to Botan which are so numerous it’s easy to see why Yoko Minamino’s sad beauty (the film’s title refers to a flower that blooms briefly in winter; an apt metaphor for our heroine) only has eyes for him. A riverside sequence in which Botan describes to Tomita the man she’s in love with only for him to fail to recognise that it’s him she’s describing is really touching.

Of course we want Botan to end up with the right man but if not Tomita, who? Without wanting to give it away the answer turns out to be a character painted as little more than a big kid but whose love for Botan is sincere. What’s interesting (and testament to the skill of the writing and direction) is that such a move is a tough sell for any viewer because the chemistry between Botan and Tomita is already so strong. So how do you convince an audience that someone else has captured Botan’s heart? The answer is to show Botan willingly putting herself in harms way to protect this man. So, in the middle of the climactic battle that’s exactly what we get and it’s a moment that’s nasty and horrific but absolutely works. All in all Midwinter Camellia is a yarn in the hands of an old master. Furuhata’s classical style of direction (i.e., invisible) does everything required to service the story and absolutely nothing to get in the way of it.

And it’s not like he doesn’t know how to flex some directorial muscle either. One of the highlights of the big fight is a thrilling tracking shot as Tomita and Nioyama crash through a succession of thin walls in the brothel, scattering Tamura’s goons like pinballs as they go. With good supporting performances – the child actor playing Tomita’s kid avoids the cute brat curse as an amusingly pithy observer of his Dad’s foibles, Nagare Hagiwara’s well dressed villain is a rat from head to toe, plus lots of quite fascinating local colour from a time when modern western fashions sat side by side with traditional Japanese ones – Midwinter Camellia is an easy watch for non-Japanese viewers. The closest comparison I can make is with movies like Yoji Yamada’s The Hidden Blade and The Twilight Samurai. Films which certainly had action in them but were primarily humanist dramas with an intense interest in and affection for ordinary working people. So it is here.