Last Updated on January 25, 2021 by rob

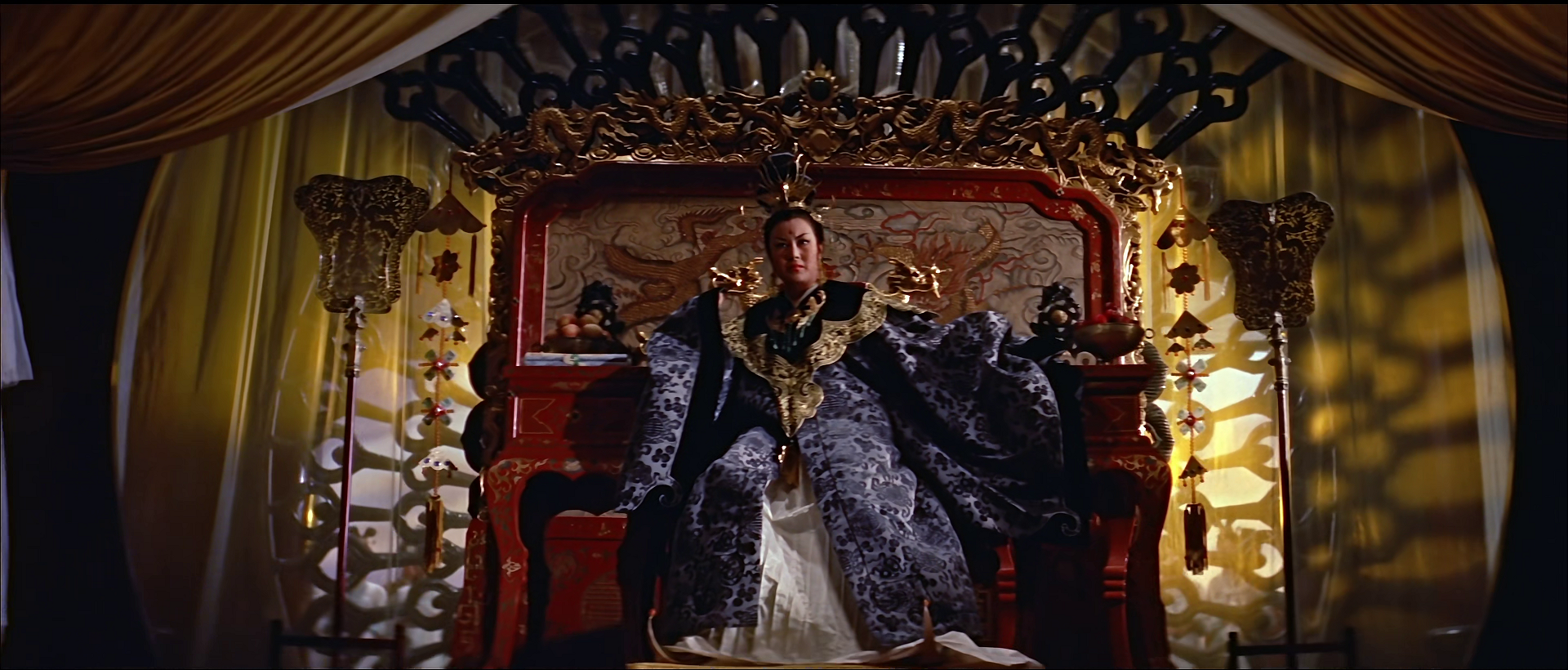

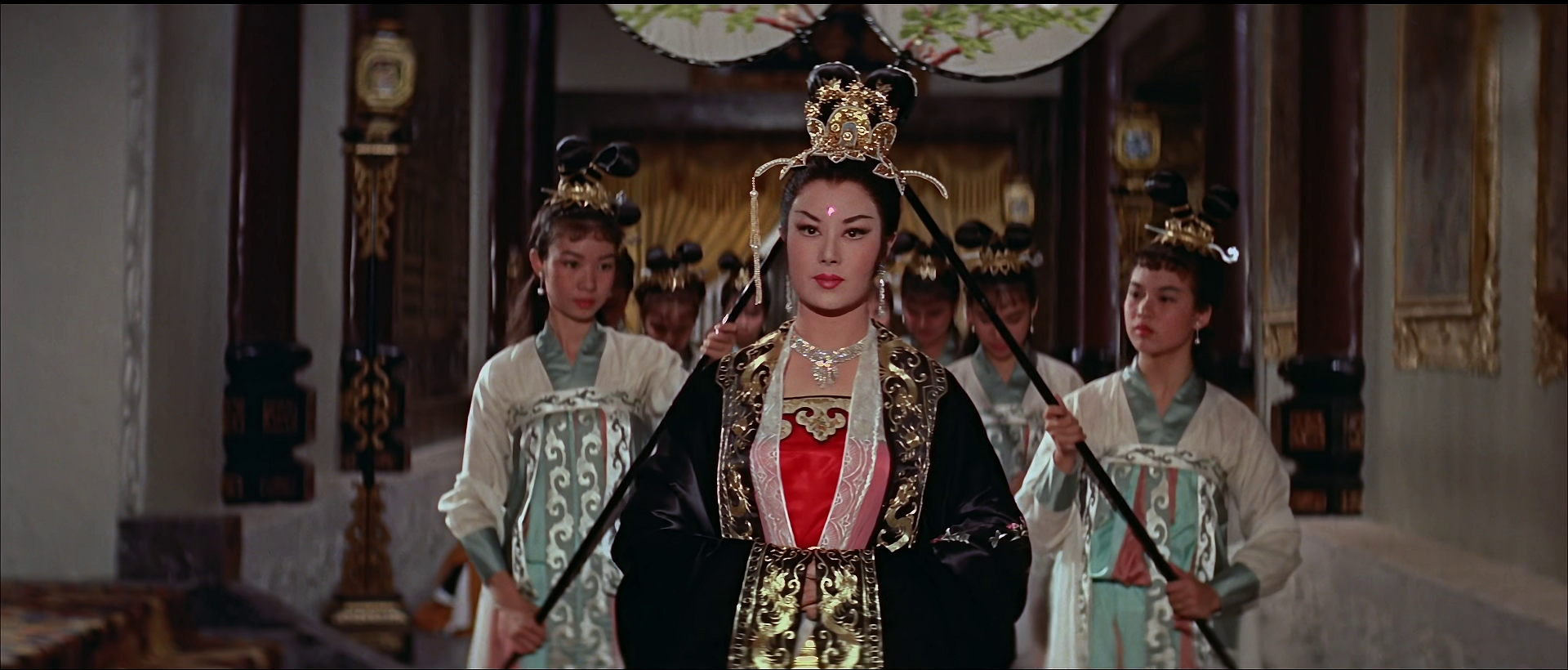

Gob-smackingly gorgeous and lavishly staged drama, in colour and widescreen, about the rise, reign and fall of China’s first and only female ruler Wu Tse-Tien (Li Hua Li). Well acted and well-written, its chief strength is a satisfyingly even-handed portrait of Wu herself thanks to a compelling performance from veteran Hong Kong superstar Hua Li. It’s certainly possible to see Wu as a villain – especially in the early stages when the finger of blame for the deaths of anyone standing in her path to power seems to point directly at her – yet later revelations cast unexpected doubt on our assumptions and suggest that much of the animosity and plots to usurp her actually stemmed from unhappiness at her liberated attitude and refusal to buckle under to a traditionally male dominated society.

Illustrating this point there’s a great scene where Wu refuses to deal harshly with a group of nuns accused of seducing young men. She sees the double standard at work that lets men do what they like while punishing women for the same behaviour. Not only does she insist that society’s rules be rewritten to redress this imbalance – to the horror of her male advisor – she then, in a delightful twist typical of this woman’s character, threatens him with beheading and when he refuses to apologise, is so admiring of his principles that she sets about seducing him! There’s also Wu’s complex relationship with Wan Er (Grace Ting Ning), the 14 year old orphan whose father and grandfather were beheaded by the Empress after plotting to kill her and whose honesty and integrity so impresses she becomes Empress Wu’s chief aide and stays by her side to the end even as the girl becomes part of a conspiracy to overthrow her boss.

The film doesn’t stint on depicting how harsh the Empress could be either. During her reign she even has her own son beheaded for plotting against her. But for every horrific act the script counters with a positive and slowly but surely our sympathy for this woman increases. The population doubled under her reign, she showed concern for the plight of commoners even as her male courtiers expressed horror at the idea of the country’s ruler personally intervening in the affairs of the hoi polloi and she demonstrated a shrewd grasp of morality and ethics. Set against this – smartly shown in quick cutaways to the persistent grousing of barflies and drunks in the local taverns – is the persistent sentiment that the country’s going to hell simply because there’s a woman in charge.

Even if the relative sophistication and wordplay of Empress Wu’s dialogue is sometimes poorly served by the English subtitles and various supporting characters insufficiently identified, none of these weaknesses much detract from a compelling and sumptuously mounted historical costume drama. In the film’s climactic sequence, in which having narrowly suppressed one rebellion the now elderly Empress – alone in her court as the sun sets and the shadows lengthen (magnificent lighting here by Japanese cinematographer Tadashi Nishimoto) – finds herself belittled for being a woman by the ghosts of her enemies but silences them all with a cry of ‘I forbid you to laugh’, it’s hard not to be moved by the accomplishments of this tough yet fair-minded woman, China’s first and only female ruler. This is one of the great Shaw Brothers movies of its decade.