Last Updated on October 24, 2020 by rob

On the eve of his release from prison after killing a father and his child in a car crash Oida (Tatsuya Nakadai) accepts an offer of 15 million yen from his cellmate Sengoku to kill three men with no questions asked. But when the first of his intended victims is killed by two hitmen the deceased man’s infant daughter Tomoe refuses to leave Oida’s side. Then Oida re-encounters Teruko, the widow of his hit and run victims, now reduced to working seedy clubs as a hostess. Confronting Sengoku and the killers in a violent showdown a mortally wounded Oida finds a way to make up for the suffering he’s caused Teruko and Tomoe.

I enjoyed this. It’s a strikingly photographed b/w crime yarn with an easy to follow story and a cast of suitably tormented characters. In its setting of back alleys, strip clubs, scrapyards, boxing gyms, rooftops and industrial plants it’s very much in the mould of the kind of crime movies directors such as Teruo Ishii churned out early in their careers. If you’ve seen any of the Japanese imitations of American crime films of the late 50’s or early 60’s such as in the ‘Line’ series – Black Line (1960), Sexy Line (1961) and Fire Line (1961) – you should feel right at home with this. However there are also some notable differences. Yasuko Ono and Hideo Gosha’s screenplay imposes an unusually fatalistic theme on the action in the way it sets up virtually every character as a poor schlub desperate to escape the misery they’re mired in only to see all their efforts come to naught. Oida’s meeting with Sengoku’s girl Utako, the way he appears just after she kicks over a bin full of bones for a hungry dog, is an especially sharp visual metaphor for our hero’s character.

Hired as a killer but unable to conceal the regret he feels at having destroyed Teruko’s family, Oida embodies a redemptive theme that gets worked through to satisfying effect. When one of Sengoku’s men, Motoki, is murdered by the bad guys and his 8 year old child Tomoe stubbornly refuses to leave Oida’s side we sense right away that hired killer or no Oida must be a decent sort. But just you try telling that to Teruko, the widow forced into working seedy clubs as a hostess and who hasn’t lost any of her burning hatred for the man who destroyed her life when she literally collides with him in a back alley. The bridge between these two turns out to be Tomoe (a scene stealing performance from this child actress) in a sublimely staged sequence wherein she, Teruko and Oida unexpectedly encounter each other on a snowy winter’s evening and the possibility of a solution to their respective woes – enhanced by Masaru Sato’s score, a melancholic sax and harpsichord combo never more evocatively used than here – presents itself.

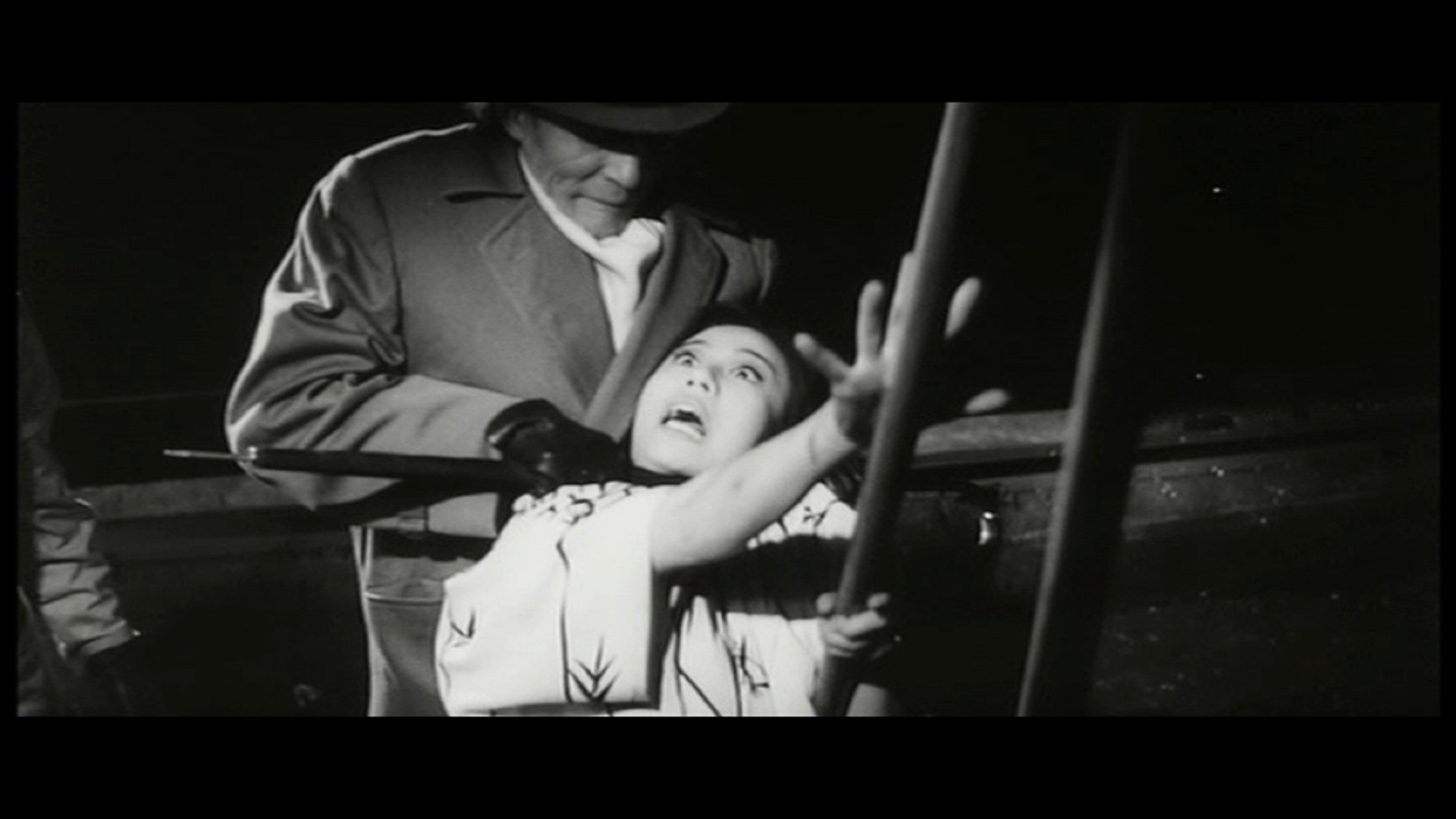

It’s all quite emotionally involving and the personal issues of the principal characters combine effectively with the film’s hard boiled crime action as Oida pursues the three members of Sengoku’s gang only to find a pair of Hong Kong drug dealers (the leader played by the cadaverous actor Hideyo Amamoto, so good as the villainous mastermind in Kihachi Okamoto’s dazzling 1967 film Age of Assassins) constantly one step ahead of him. Although the fisticuffs are a touch – shall we say – unpolished, Gosha nevertheless makes the two men from Hong Kong a credible threat. The murder scenes have a vicious edge to them and he sets the action in some really atmospheric locations. A chase and double murder in the middle of the night at a water recycling plant is a terrific little setpiece as is a juicy back alley catfight between Teruko and Utako in which the actresses do a convincing job of throwing each other around.

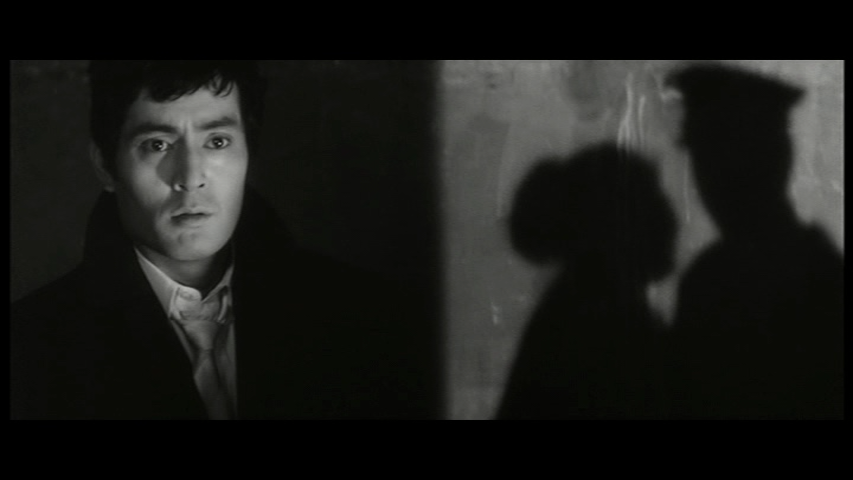

For the robbery which opens the film Gosha shrewdly inverts the positive image of the film stock into a negative one. This is not only visually eye-catching but proves an effective way of muddying the waters and adding a touch of intrigue as to who’s who and what’s just happened. We need this otherwise the viewer would be too far ahead of Oida in figuring everything out. The cast are engaging but the real stars are Gosha’s dynamic screen compositions and Tadashai Sakai’s gleaming noir-ish cinematography. In fact the visuals are frequently so striking that it inadvertently highlights Gosha’s weakness as a filmmaker in that he’s clearly a director primarily interested in technique but he’s really not much of an actor’s director.

I mean Tatsuya Nakadai has the most marvellously expressive features but he has a tendency to ham unless he’s under the guidance of a strong director and there are more than a few times here where his performance seems a bit overdone. It doesn’t ruin the movie or anything but one is aware of it and it’s something you feel a more attentive director might have corrected. But that aside this a most engaging tale of wounded souls crossing and re-crossing each other’s paths against a backdrop of seedy clubs and dark alleys and ultimately finding redemption even as the story remains true to its noir roots.