Last Updated on October 1, 2020 by rob

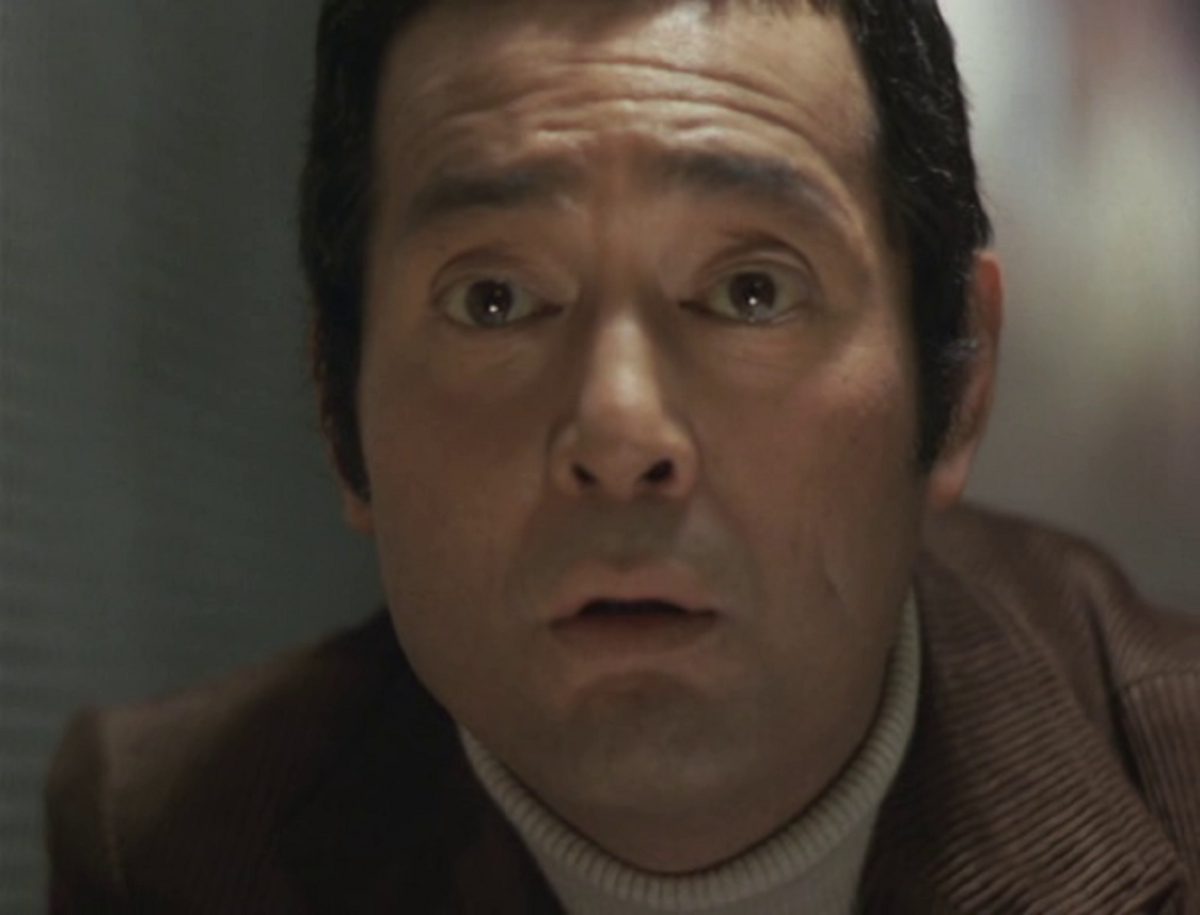

After Professor Hyodo makes claims about UFO’s and aliens he disappears and TV reporter Minami (Tatsuya Nakadai) is assigned to investigate. Minami’s search turns up rumours of people whose blood has turned blue after exposure to UFO’s and their forcible incarceration and vivisection in secret US detention camps. But Minami’s attempts to reveal the truth face a global conspiracy by politicans to seize total control via an orchestrated campaign of hysteria and violence aimed at demonising those with blue blood.

The ghosts of WW2 are never far from the work of Okamoto – a University graduate whose entire class was drafted into the Pacific war in 1943 and of whom Okamoto (sent to work in a factory) was one of its few survivors – but Blue Christmas represents something of a departure. For starters it’s not a war pic but a glossy, contemporary SF/globe-trotting conspiracy thriller not a million miles away from Fukasaku’s Virus and its drama is fuelled not by a Japanese experience of the war but a European one, namely The Holocaust. So, as Nakadai’s reporter travels from Japan to New York in search of a missing scientist and hears tales of secret facilities in which people with blue blood have been interrogated and then lobotomized to stop them talking, of Siberian concentration camps and underground resistance movements, the film shows promise.

A sense of constant surveillance and menacing figures in shades who seem to know our hero’s every move conjures up agreeable echoes of The Parallax View and Three Days of the Condor. The snappy pacing of the first 45 minutes or so works fine. But too many undeveloped sub-plots ultimately weaken the drama. Just to give you some examples of those; Nakadai finds himself exiled to Paris with his family after his superiors shut down his investigation. A promising young actress is framed for drug taking and later commits suicide after Nakadai carelessly lets slip to his boss that there’s a rumour she has blue blood. UFO sightings continue to increase as vast swarms of saucer and cigar-shaped objects are seen around the world. An elite soldier in the Japanese military finds himself in love with Saeko, a blue blood woman he’s been ordered to kill.

Oh, and there’s bizarre American rock band called The Humanoids who preach about something major happening on Christmas Eve and whose song Blue Christmas is topping the charts everywhere. Now any one (or two, or three, or four!) of these stories would be sufficient to explore Okamoto’s chosen themes of prejudice and global media manipulation (it’s a sign of the times that after all those pro-UN Japanese SF/Monster movies of the past decade, that same organization is shown here in a distinctly darker light) but even though I had no problem with the film’s hefty 123 min runtime the sheer number of sub-plots can’t disguise the fact that the film lacks a central focus, a single point of view.

In fact it’s all over the place. It’s great to see Nakadai in a contemporary piece instead of the samurai roles we know him best for but his journo virtually drops out of the pic altogether by the halfway mark and the film can’t entirely avoid both the travelogue aspect – there’s an ill-judged sequence in New York of Minami pounding the streets and accosting complete strangers in his search for Professor Hyodo that doesn’t work at all – or a woeful foreign language segment in which Nakadai and a French actor attempt a conversation regarding a mysterious event rumoured to happen on Christmas Eve (Okamoto’s version of Kristallnacht) in such broken English you need subtitles to understand what they’re saying. As for where the UFO’s come from and what they want and who’s actually behind this conspiracy to seize global power – that’s never explained either. Interesting issues are raised. We learn that developing blue blood purges one of bad tempers and irritations. Does that mean then that the UFO’s are benevolent? Are the blue bloods a superior breed of human? How have The Humanoids, a group of rock musicians with a lousy record, come to hear of this global conspiracy anyway? No answer is forthcoming.

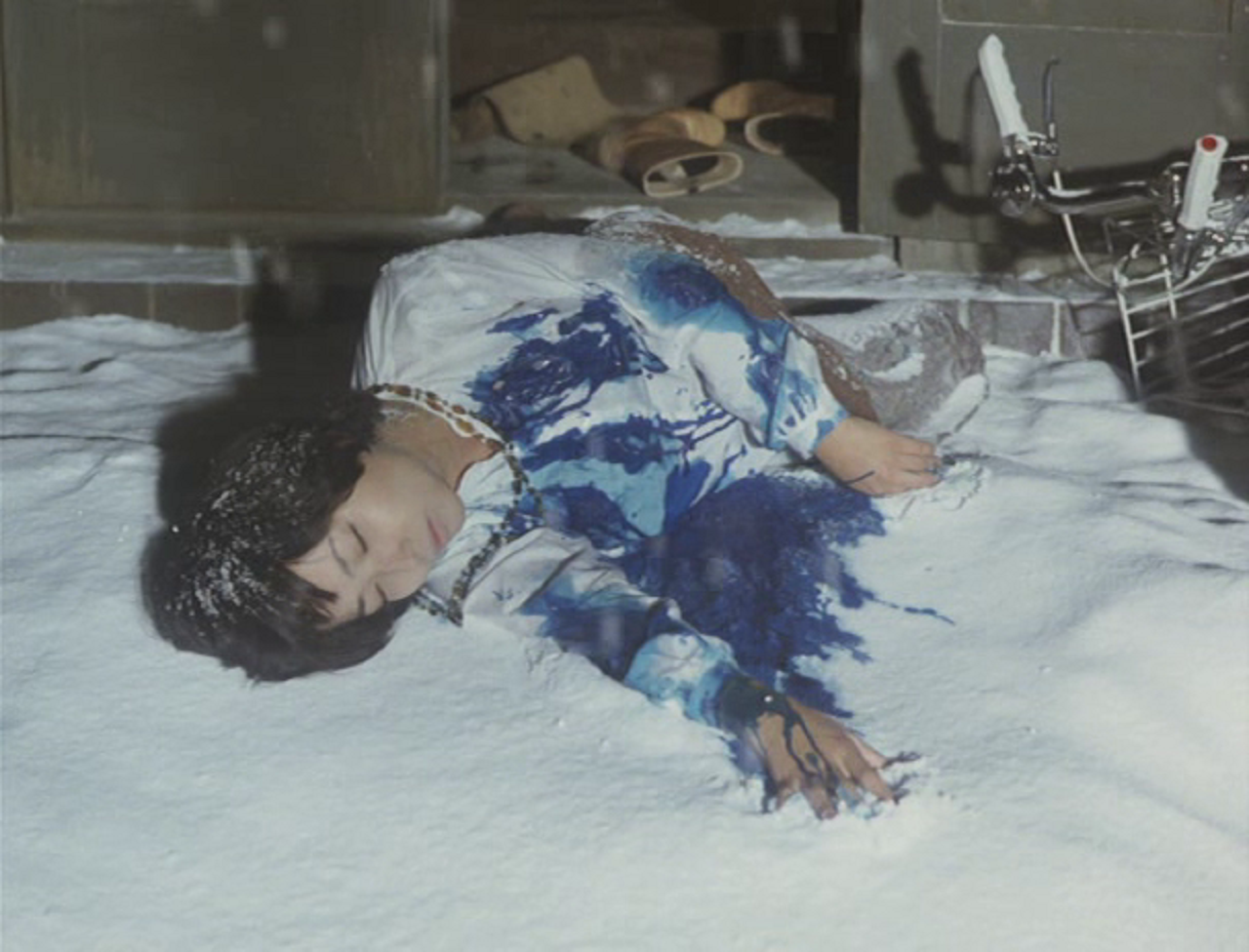

The effect of all this is simultaneously intriguing and frustrating. The last hour of the film switches focus from Minami to a soldier tasked with spying on a blue blood sweetie named Saeko whom he develops an affection for. But it doesn’t work because we don’t know these characters or their circumstances well enough. A revelation that certain blue bloods are being deliberately left alone (Saeko being one) so they can band together into groups the government can then exploit as organised enemies of the state is an especially knowing touch. The scenes of people around the world on Christmas Eve preparing for the festivities, unaware of the imminent global massacre, are suitably foreboding. As children and adults alike are gunned down by security forces there’s no doubting Okamoto’s empathy with the victims of this terror – best conveyed in a grim but touching climax in which the camera tracks a stream of blue blood from Saeko as it trickles through the snow to intermingle with the red blood of her lover – but Blue Christmas is more a mildly diverting experience, an interesting failure than a successfully realized story. It does have its moments though.