Last Updated on September 29, 2020 by rob

In the near future waves of anti-matter from Neptune wreak havoc on Earth. Astronaut Roy McBride (Brad Pitt) is enlisted to help since the source of the shockwaves is believed to be a spaceship captained by Roy’s father, Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones) and long believed to be lost. But as Roy embarks on a perilous mission to Mars he uncovers secrets about his supposedly heroic father which mean he must make the journey to Neptune in order to learn the truth.

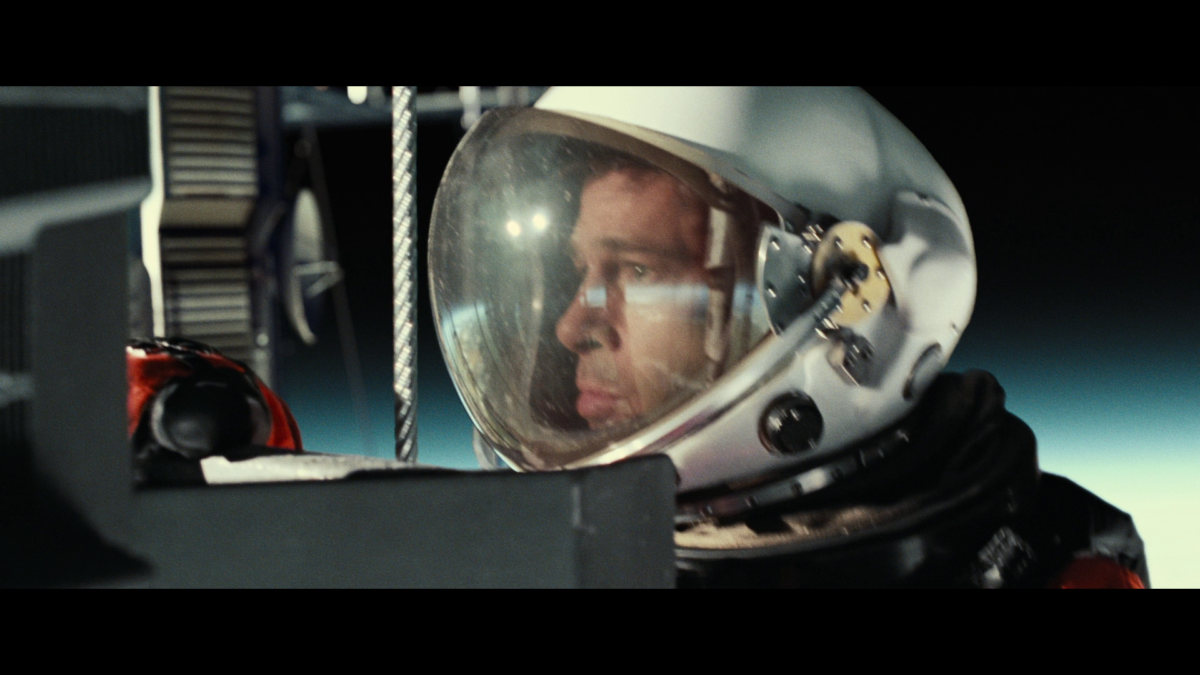

Big questions about man’s place in the universe combine with a tale of the human heart in this ambitious SF movie that I thought was really pretty terrific. Brad Pitt plays an astronaut distinguished by having a pulse that never races (the cause of which, it’s implied, is the loss of his father on a space mission when he was just a child) so he never gets excited or gives in to displays of emotion. That’s one hell of a challenge for an actor since Pitt has to find ways to keep our interest while playing a character who is essentially inexpressive and unemotional. But it works because there is something inherently likeable about Pitt and he brings a kind of soulful quality to his performance. Once he learns that his father may be alive you can sense the pain aching inside him and empathise with the urge that drives him all the way to Neptune.

Brief flashbacks showing us Roy and his wife (Liv Tyler) underline how estranged this man is, not just from his wife, but from any kind of emotional intimacy with anybody. He’s like a Vulcan and just as Mr. Spock’s analytical mind was used by Star Trek’s writers to illustrate the foibles of humans there’s some of that same quality here as Roy’s dispassionate mind is able to spot, analyse and compensate for the weaknesses of his fellow astronauts (not least in a hair-raising emergency landing on Mars) because, like Spock, his mind isn’t clouded by emotional trauma. Some of the images – in particular the sight of Roy in his astronaut suit pulling himself along an umbilical cable through a dark tunnel like some hi-tech baby in a womb – prove so resonant that one of director James Gray’s greatest achievements here is to make an epic journey into outer space feel like an interior exploration into Roy’s heart.

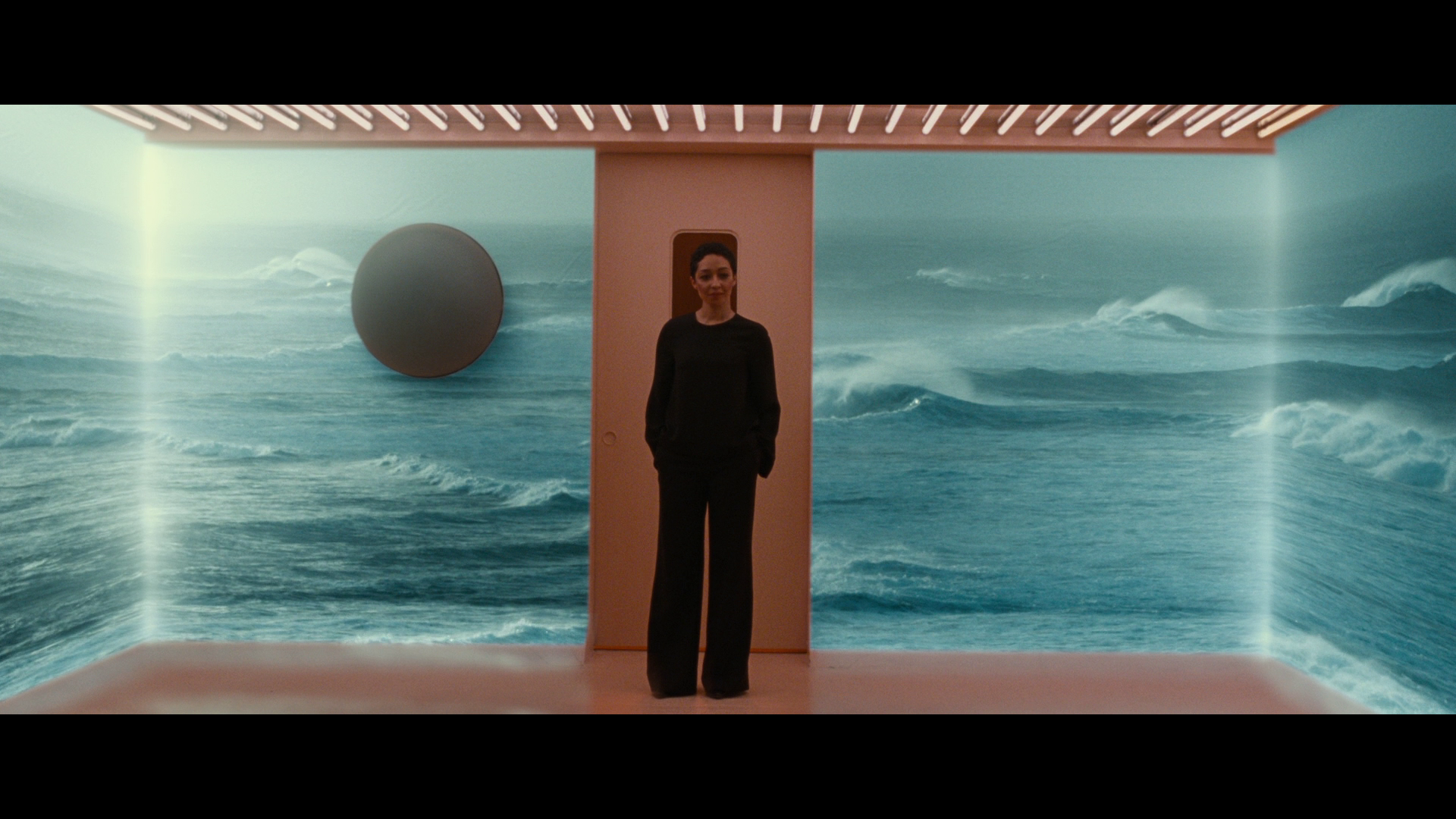

Although the film has its share of mystery (such as an encounter with a derelict ship packing a gruesome surprise), intrigue (is Roy fated to follow in the footsteps of his murderous father?) and action on a large scale (a lunar rover chase is deadly yet beautifully eerie in execution) there’s a languorous, dreamy rhythm to the storytelling and an intimate, personal quality so palpable it even allows director James Gray to get away with dismissing the nominal cause of those shockwaves, that have gotten the audience interested and sent Pitt on his mission, with no more than a throwaway line from Roy’s Dad. Donald Sutherland as a former astronaut and Ruth Negga as a Mars-born base commander have small roles but lend welcome warmth and humanity to Pitt’s quest through a world that seems pointedly inhuman.

Ultimately the drama of Ad Astra comes down to a conflict between mind and heart and – in the father/son drama that shapes the climax – a protagonist who must make a choice between the two. I found it fascinating the way Gray sets all this up because Roy seems almost like a Blade Runner replicant, a slave who does what he’s told and goes where he’s ordered without question. And in the constant psychological testing he’s required to complete at every stage of his voyage from Earth to Moon and then to Mars we get what seems to me a sly inversion of Blade Runner’s Voight-Kampf test in which any indication of emotion is perceived as making Roy a threat to those around him. The astounding retro visuals of Gray’s film conjure up a world set several hundred years hence in which it looks as though the Apollo space programme never ceased.

There’s clearly a debt here to 2001: A Space Odyssey as well as the general aesthetic of early 1970’s SF cinema. Yet at the same time Gray’s film feels fascinatingly like an implicit rebuke to Kubrick’s. Tommy Lee’s father character would have been right at home on board 2001’s Discovery yet the film’s sympathies – and ours – are wholly with a man who rejects the primacy of scientific exploration and technological analysis over that of basic human bonds. The final scene in which Roy’s emotionless answers to his psychological test are slyly intercut with what he’s really thinking underline the profound and most welcome change in this man. Welcome back to the human race, Roy!