Last Updated on November 14, 2020 by rob

In the last months of WW2 a tiny village becomes home to two refugee families, the Sonobes and the Shimizus. But after pretty Yuri Shimizu (Mariko Kaga) refuses to marry the mayor’s son, a local war hero named Takamori (Bunta Sugawara), malicious rumours put about by the latter have the villagers blaming the new arrivals for every incident no matter how trivial. And when Takamori – whom the Sonobes know is actually a war criminal – forces himself on Yuri her desperate act of self-defence inflames the locals and the two families are forced to take up arms to defend their homesteads against the villagers.

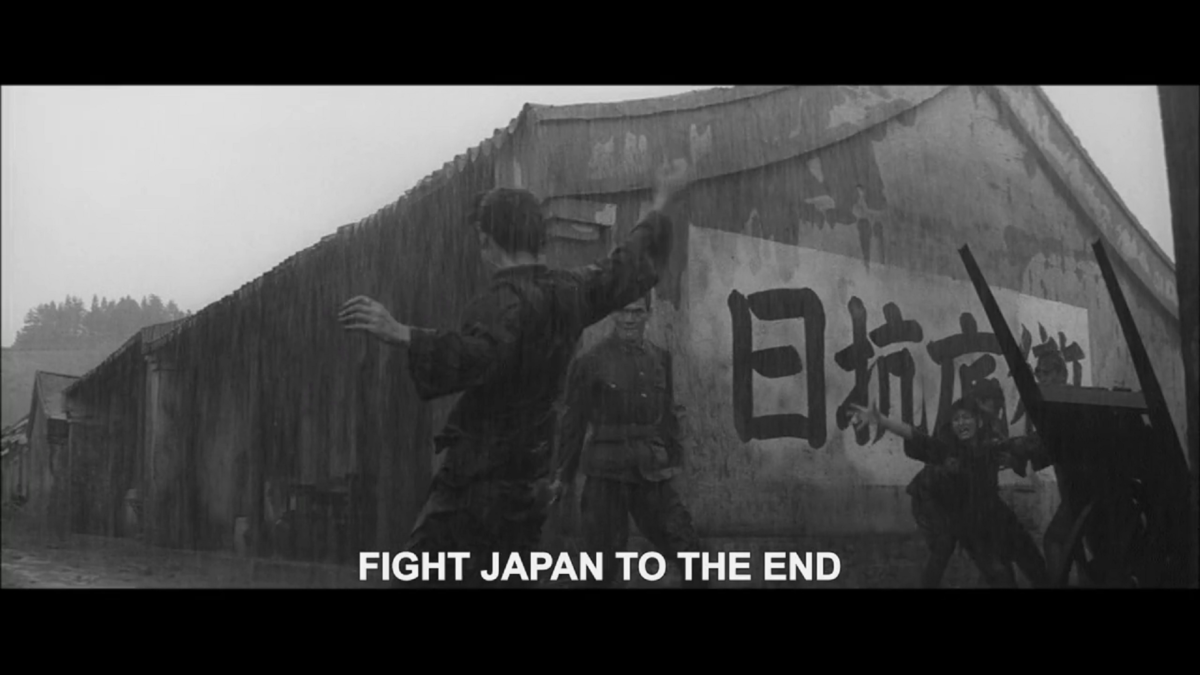

A powerhouse movie with a plot that could have come straight out of an American western. The predominantly female cast in which a new generation of actresses represented by Shima Iwashita and Mariko Kaga share the screen with the great Kinuyo Tanaka are all excellent. Their nemesis Bunta Sugawara (best known as the star of endless Kinji Fukasaku directed Yakuza movies before showing a softer side in the Trucker Yaro series) is a most frightening figure; a rigid, unbending martinet with a fanatical gleam in his eyes and the epitome of the crazed military types that took Japan into the abyss during that period. One powerful setpiece follows another. Amongst them the shock moment of recognition between the Sonobe’s son Hideyuki (Go Kato) and the loathsome Takamori that plunges us into a combat flashback from Manchuria. In a masterfully staged tracking shot of two Chinese civilians fleeing from their pursuers through torrential rain we witness Takamori murder one and then drag the survivor off to be raped in front of Hideyuki’s horrified eyes.

Another sequence in which Takamori on horseback approaches Yuri on a mountain path under an ominous skyscape (honestly, Kinoshita’s attention to roiling cloud formations here could give Kurosawa a run for his money!), the only sound the trot-trot of the horse growing in volume as he approaches, is a sequence of sheer tension. We know all too well what’s going to happen when he reaches her but that doesn’t make it any the less easier to sit through. The film is directed with effortless mastery by Kinoshita using a succession of wide master shots with sparing use of mid shots or close ups. His blocking of actors in the frame never strains for attention and yet every composition feels perfectly judged. Cinematographer Hiroshi Kusuda’s location work is flat-out breathtaking. The opening colour shots of the farming village embody the essence of a community at peace with itself. When the movie switches to black and white for the bulk of the story his images of this remote village encircled by dense forest and snow-capped mountains really help evoke the fable-like quality implied by the film’s memorable title.

Also memorable is the unusual score by the director’s brother, Chuji – a weird rhythmic buzzing that sounds for all the world like Australian aboriginal music. Just considered as an exercise in tension the film is bang on target but its vice-like grip and visceral impact owes much to its wartime setting. The villagers don’t turn into a mob hellbent on murdering the Sonobes and the Shimizus just because Takamori was jilted, or even because their crops were ruined. No, they go beserk because of the grim news filtering through to them about the state of the war. The deaths of every one of their sons who were sent off to fight with promises of glory and the news of the A-bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Govt’s impending capitulation, turn their grief into a raging torrent of emotion that needs an outlet and – manipulated by Takamori and his vengeful father – finds it in blaming the new arrivals for their woes. The final act as the two families attempt to flee across a mountain pass pursued by bloodthirsty villagers who’ve lost all self-control is an absolute barnstormer.

So acutely does Kinoshita nail the turbulent feelings here – the villagers with their blood up, the families who will do whatever they have to do to protect their kin – that you feel like you’re being swept away by a tidal wave of emotion. During the body-strewn climax an image of a bullet slicing the heads off a row of wheat poignantly expresses the senselessness of what’s occurring. It’s a genuinely cathartic ending and when the film flips back to colour and its present day setting of friendly farmers from the same village all pitching in to help one another you just feel so relieved all that madness is long past. With A Legend Or Was It? Kinoshita not only made a gripping suspense drama but – in its tale of ordinary folk whose emotions are manipulated by unscrupulous leaders and transformed into crazed killers – a metaphor for what happened to Japan’s people during the war. This is one helluva film from one of Japan’s greatest and most versatile directors.