Last Updated on October 17, 2020 by rob

When home carer Sawa’s (Sakura Ando) employer requests her to sleep with her dying father she agrees but the result proves a disaster in more ways than one. Finding herself homeless Sawa accosts a series of lonely, elderly men ranging from karaoke bar resident Yasuo (Tatsuo Inoue), grumpy car mechanic Shigeru (Toshio Sakata) and retired academic Professor Makabe (Masahiko Tsugawa). Eventually Sawa ends up back where she started in a chance encounter with Makoto (Nozomi Tsuchiya), the mute teenage son of her first employer, who’s at the end of his rope struggling with personal demons. Can Sawa make a difference?

An entertaining and satisfying humanist drama with a hilariously deadpan performance by the wonderful Sakura Ando as the carer and a string of tasty supporting performances from the old codgers whose lives she affects. Along with its performances the film’s unpredictability – it opens with a blunt depiction of what it’s like to deal with the incontinent elderly and then spirals into a blackly humorous piece of Grand Guignol horror (all this in the first 20 mins!) – is one of the great strengths of its whopping three and a quarter hour runtime. For half the film we’re never entirely sure of Sawa’s motives. We certainly feel sympathetic toward her when she loses her job and then her savings but Ando combines her caregiver’s amusingly firm manner toward her protesting charges with a hint of something wilder (“Your cock is the size of a thumb!” she screams point blank at a Yakuza thug before headbutting him), a quality that leaves us slightly wary of her.

Anyone who saw Ando as the broken schoolgirl turned manipulative monster in Love Exposure will know just how effectively this actress can combine both tender vulnerability and fearsome rage in a character. When, later in the film, her stay with Professor Makabe is interrupted by the arrival of his daughter who intends to take over the house you do find yourself wondering if Sawa’s expressionless reaction to this challenge to her position is a harbinger of murderous intentions. But Sawa’s charming chemistry with the gentlemanly Yasuo – whom she practically manhandles into a karaoke room for a night because she needs drink, food and a roof over her head – is such a delight and their sweet farewell the next morning – the unspoken feeling between them that if circumstances were just a little different these two could live happily together – does much to earn our trust.

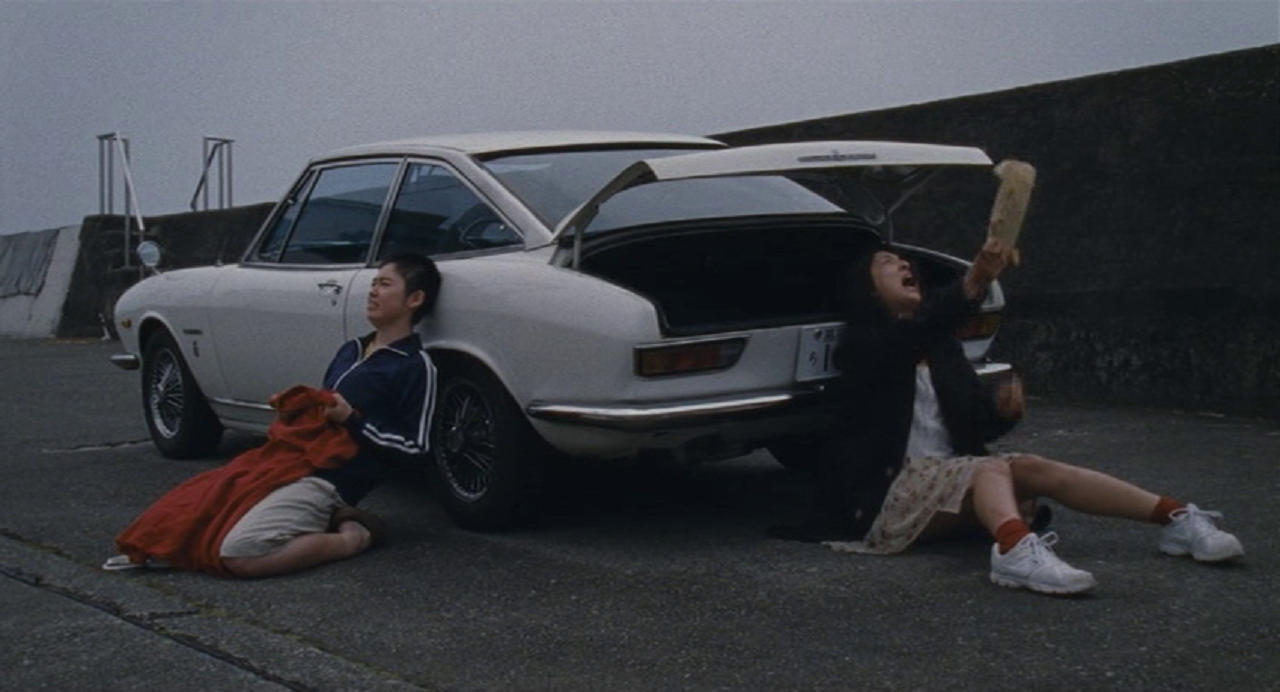

So it goes with her next encounter, as Sawa gradually wins the friendship of the cantankerous Shigeru (a sort of Japanese Victor Meldrew) whose outwardly tetchy demeanour proves no more than a front for someone so sensitive he can no longer cope with the world around him. However Sawa’s astute guidance not only resolves Shigeru’s personal problems but leads to a delightful reward when Shigeru – having allowed Sawa to drive him to the retirement home he intends to spend the rest of his days in – leaves her his classic Isazu 117 Coupe. At this point the film seems to have settled into an agreeable groove. Sawa’s going to help a succession of elderly men and reap the rewards, right? Well, not quite. Once Sawa meets Professor Makabe she unexpectedly turns into much more of a supporting character in a lengthy tale of a man tormented by his wife’s senility and his own past.

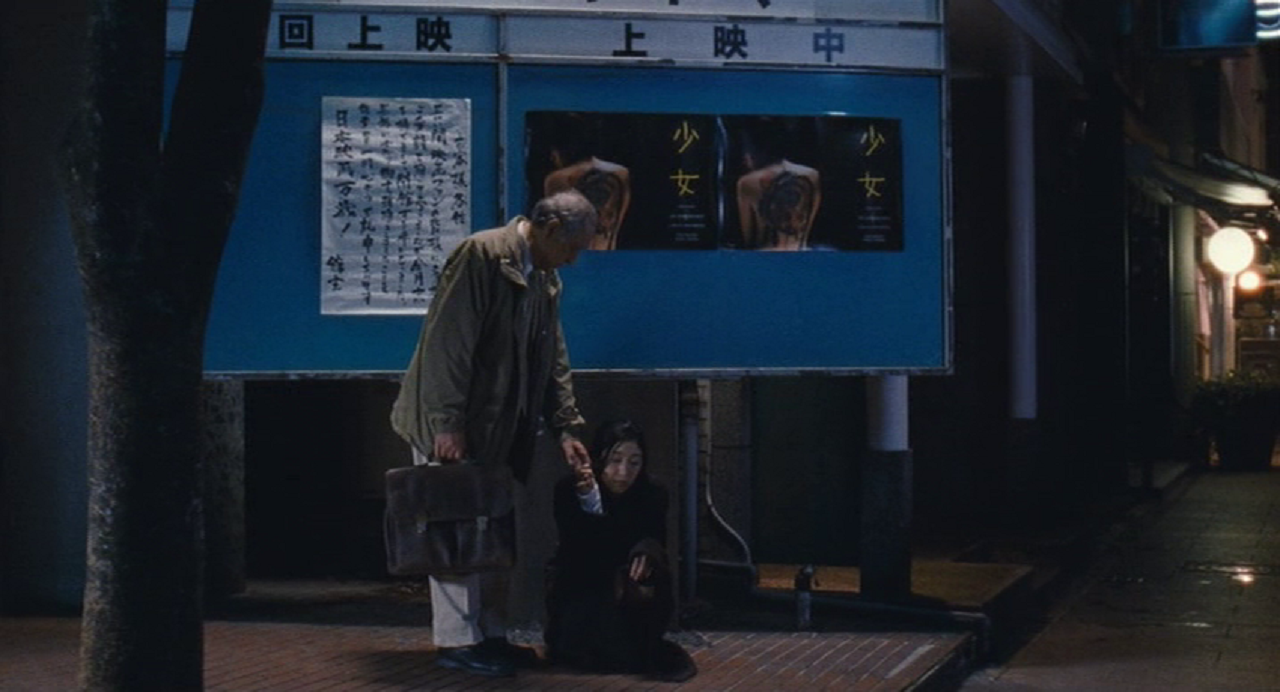

This section also casts more light on the intriguingly asexual figure of Sawa herself. This is a woman who allows the men she meets – men for whom the flesh may be weak but the spirit more than willing – to grope her before firmly letting them know when they go too far. But once Makabe takes her to the cinema to watch a showing of An Adolescent (a film directed by and starring none other than the Ando’s own father, Eiji Okuda), Sawa giggles uncontrollably at a sexual tryst to the point she’s thrown out of the cinema. It’s a scene that starts off funny but then becomes disquieting because of its implication that though Sawa may be physically a grown woman, emotionally she’s still a child. There’s a reasonant capper to this as Makabe comes out of the cinema to see Sawa sitting on the ground and just very gently takes her hand.

You can definitely feel some of the movie’s earlier fizz dissipate at this point as it becomes clear that this isn’t going to be another case of Sawa running comical rings around some crusty pensioner. But director Momoko Ando (Sakura Ando’s sister) knows what she’s doing and as we learn about Makabe’s traumatic experience in the Navy during WW2 the film’s theme and Sawa’s purpose come into focus (so, incidentally, does the film’s curious title). A scene in which Sawa breaks down and cries listening to Makabe’s message poignantly illustrates her own limitations (as persuasive as she is she couldn’t stop Makabe from wanting to join his wife in death).

All of this neatly sets up the third act as a hypothesis put forward by Makabe about modern Japanese people is tested in the shape of a tormented soul (Nozomi Tsuchiya) whose life hangs in the balance dependant on Sawa’s actions. More than anything else in the movie this is all very deliberately paced but it pays off in a funny yet moving scene in which Sawa and the teenage Makoto end up back to back and crying their eyes out for entirely different reasons. Ultimately what makes the movie so rewarding is that this isn’t, as first appears, a film about how the lives of some elderly men are changed by a woman, rather, it’s about how their collective actions change a woman and in so doing give purpose and meaning to her essentially aimless existence.