Last Updated on January 24, 2021 by rob

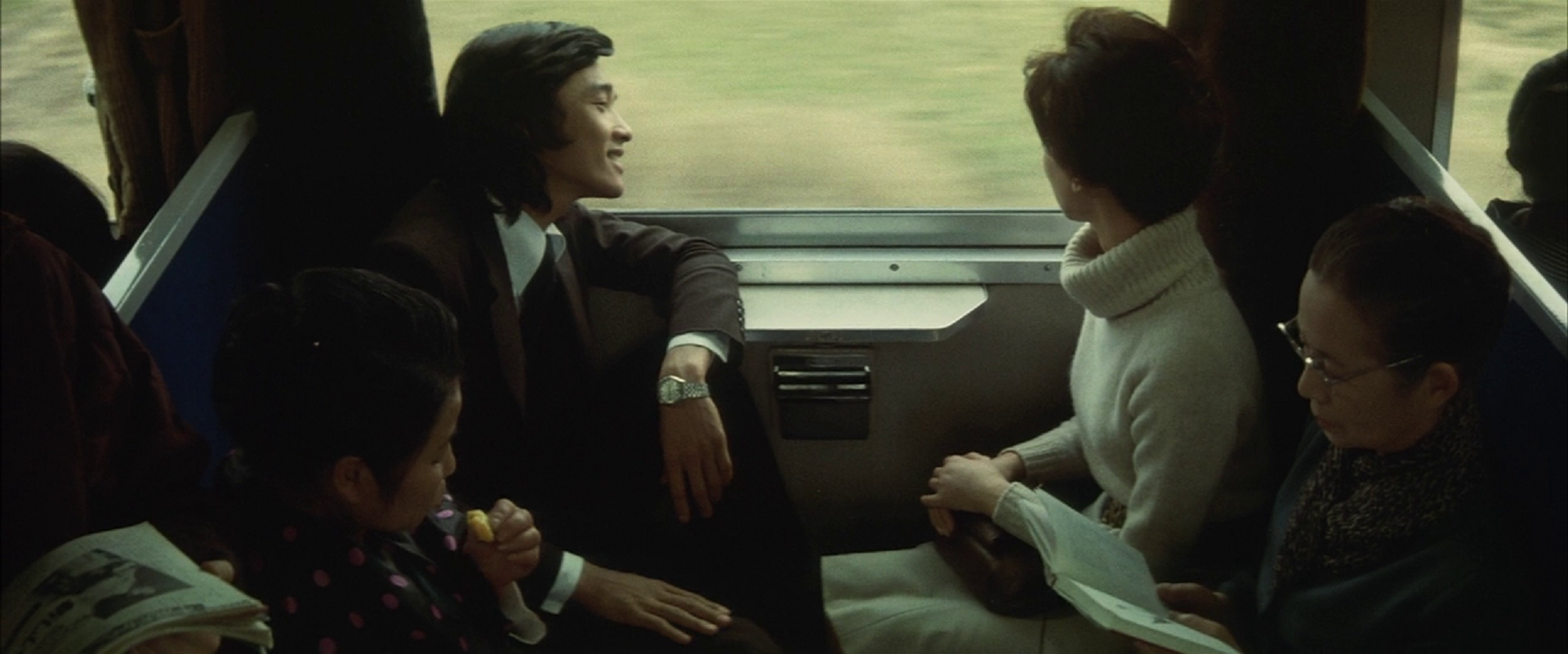

To the accompaniment of an instantly memorable score an attractive middle-aged woman (Keiko Kishi) sits alone on a park bench watching the world go by – children at play, couples arm in arm strolling past. At the end of the film we’ll come back to this scene and understand its significance but after this intriguing opening we’re on a train journey along the coast of snowy, northern Japan. On board is the mysterious woman we’ve just seen in the park. A young man joins the train and tries to engage her in conversation without success. Eventually we learn that the woman is on the way to visit the grave of her recently deceased mother. Accompanying her is a stern faced older lady whom the woman enigmatically refers to as ‘My guardian.’ When two cops bring a handcuffed prisoner on board the train and there’s a brief flashback to a shot of the woman in handcuffs we begin to get a sense of why she’s so reluctant to talk. But there’s more than one offender here and as attraction between the woman and the younger man begins to grow the stage is set for a tragedy that will take us back to that lonely figure in the park.

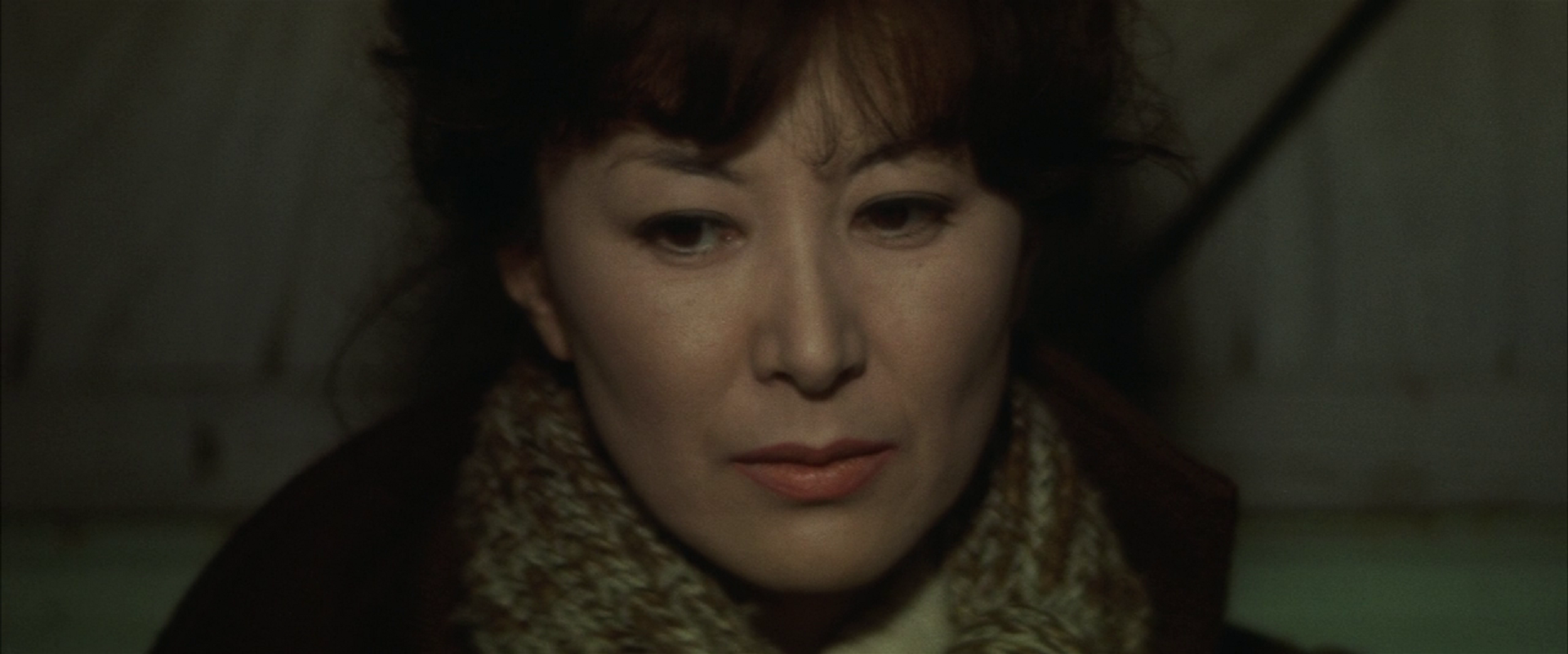

This largely train set romantic thriller, quite well known in Japan if largely unknown outside of it, won’t win over the impatient viewer but for those who can cope with films which emphasise character, performance and mood over plot this consistently engrossing study of two societal outcasts who connect builds to a knockout emotional punch and offers the pleasure of a fabulous performance from its leading lady. Keiko Kishi gives a marvellously underplayed performance here, conveying her character’s turmoil almost entirely through a seemingly infinite variety of subtle facial expressions and body language. A perfect example of the latter is when she emerges from checking in at a police station en route to her mother’s grave and her whole body just seems to shrink into itself as if ashamed to be seen in public. This inherent conflict between society and outsiders dominates all of Saito’s early 1970’s work and finds a striking expression here in a subplot that has Keiko attempting to deliver a message, in the shape of a letter from a fellow female prisoner named Kayo to her husband (Kaneto Shindo regular Taiji Tonoyama), only to find the man so full of disgust he denies ever knowing her.

Such visceral disapproval from law abiders toward law breakers needs a charismatic figure to bridge the divide and the film finds it in young Kenichi Hagiwara. He’s ideal casting as the boyish hoodlum whose puppy love for Keiko (both the character and the actress’ name) gradually disarms this woman’s defenses and convinces her to emerge from her self-imposed shell. Though the film is essentially a two-hander between Keiko and Hagiwara there’s nice support from Yoshie Minami in a near wordless turn as Keiko’s stern guardian and Rentaro Mikuni has a tasty cameo as the persistent cop (sporting a facial scar we’re told is a consequence of the Hiroshima blast) on Hagiwara’s trail. Performances aside The Rendezvous is another strong vehicle for Saito Koichi’s direction. The filmmaker always prized the visual quality of cinema above all else. None of his movies from this period could seriously be described as dialogue driven but even by that standard the dialogue here is minimal.

His combination of immaculate formal compositions using long (telephoto) lenses combined with a loose limbed, New Wave-ish approach in which hand-held camera and long takes follow the actors in the streets with the accompanying sound sometimes dropped completely in favour of the score really evokes an intensely cinematic feel on the theme of loneliness (not entirely coincidentally also one of cinema’s great themes. Saito’s technique gives the emotions that are roiling under the surface here a palpably sensual quality and he gets a great assist from Miagawa Yasushi’s achingly romantic score which plays out in a variety of arrangements from lushly emotional to trendy urban chic. I really love this score! The tense and moody tone Yasushi sets for the opening scene, in which couples and groups of kids at play in a park are contrasted with the lonely figure of Keiko, proves instantly intriguing. Then, as the camera singles out Keiko’s face and she begins to remember the events that brought her to this place, her expression changes, the score blossoms into this gloriously full on romantic melody and we go straight into the flashback that comprises the bulk of the movie. It’s a beautiful moment and a real shame the score never got released.

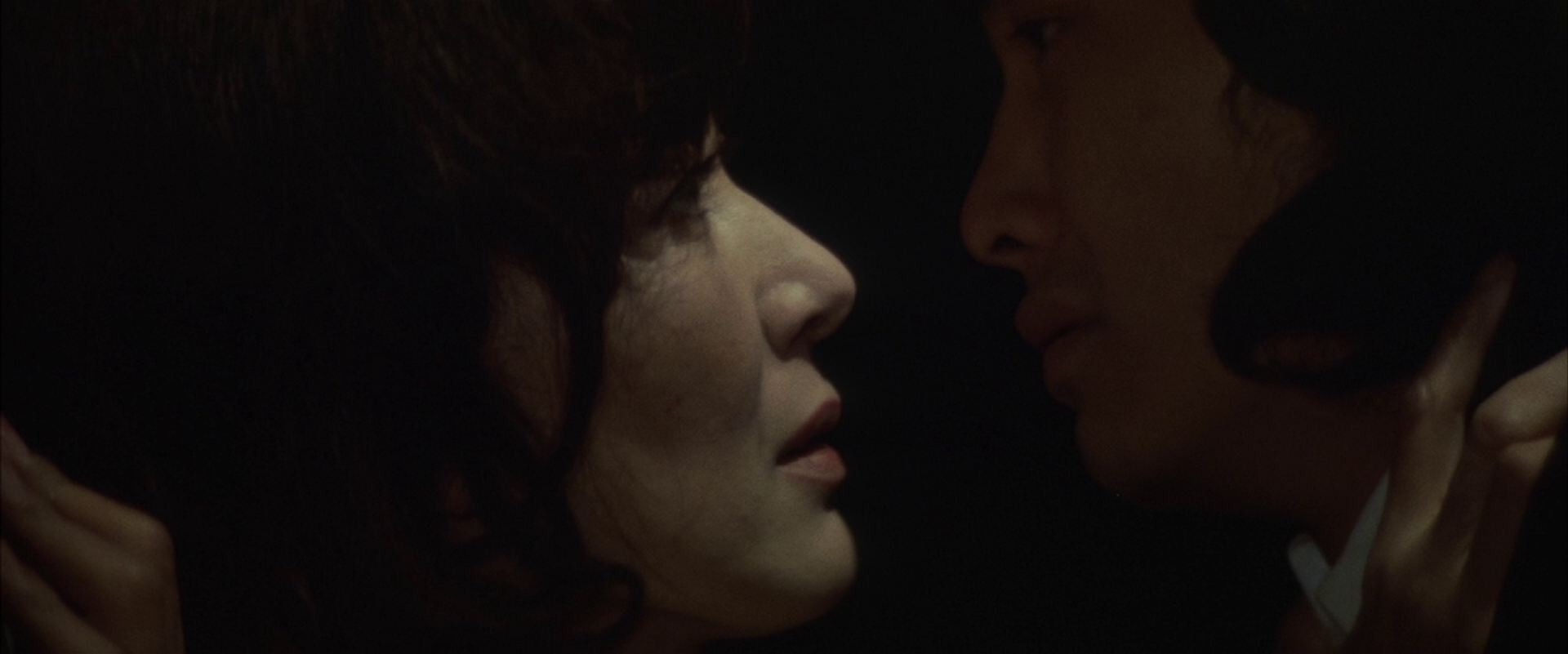

The film boasts some wonderfully lyrical touches too. A moment where Hagiwara tries to cheer Keiko up by pointing out the sight of fireflies lighting up a boat at harbour, or the scene where the two escape the train to share a long, lingering kiss as the director plays the sound of its warning bells over the kiss, like church bells at a wedding, really stir the emotions. Saito is very subtle in his handling of the thriller elements of Fumio Ishimori’s screenplay. Everything, from the sight of Keiko made uncomfortable by a newspaper headline about a drunken husband stabbed to death by his wife, or another prisoner brought aboard the train in handcuffs by a couple of detectives, to a deliveryman teasing his customer about her randy husband in a conversation overheard by our heroine, serve to poignantly remind us of her outcast status. A chase and confrontation in which Hagiwara’s character stabs a Yakuza is shot in a clipped, almost elliptical manner that nonetheless feels like exactly the right stylistic choice. Anything more spectacular would have unbalanced the film and made it seem like it was more about Hagiwara’s character than Keiko’s.

The same applies to Rentaro Mikuni’s detective who is so casually introduced that he never seems like an imminent threat even when he’s sitting in the same train carriage as the two lovers. It’s a nice bit of misdirection by Saito as well as performance by Mikuni. For this detective turns out to be very dangerous indeed and when he finally pounces it’s a brutal moment the emotional impact of which reverberates over the closing scene of Keiko alone in an emptying park and clearly fated to remain so. Keiko and Hagiwara’s chemistry here is such that it’s no surprise they were reteamed as screen lovers in 1975’s Two In The Amsterdam Rain directed by Koreyoshi Kurahara. Aside from being arguably Saito’s best film, The Rendezvous occupies an interesting position in his filmography since it both builds on and deepens elements explored in 1971’s Shadow Of Deception (about the guilt over an adulterous affair that leads to murder) and contains much that is reworked in the following year’s equally great Tusgaru Folksong.

The stars of that film, Kyoko Enami and Akira Oda, are not only dead ringers for Kishi and Hagiwara but the film utilises the same narrative structure of a story told in flashback and bookended by present day scenes and once again there’s a thriller element involving the Yakuza which simmers in the background until the climax. The Rendezvous itself also has an interesting history. Although relatively obscure to European audiences inside Asia the story has actually been remade no less than four times! The original is a South Korean movie from director Lee Man-hee called Late Autumn (1966) which reportedly no longer physically exists. Koichi’s 1972 version is the first (Japanese) remake, followed by a second from the brilliant South Korean director Kim Ki-young called Promise Of The Flesh (1975). Two more South Korean remakes from directors Kim Soo-young and Kim Tae-yong followed in 1982 and 2010 respectively. Both films reverted to the original title of Late Autumn. Given the presumed popularity of the story and its universal appeal it’s curious there’s never been a European or American remake. There’s nothing in the story that would need much in the way of changing and it could quite easily be a very good vehicle for a leading lady and an up and coming male co-star.