Last Updated on October 17, 2020 by rob

After Robert Dassa (Pierre Massimi) is viciously beaten and then thrown to his death from a rooftop car park his sister Helene (Francoise Fabian) takes over the running of his nightclub but is brutally assaulted by the same men, thugs seeking to use the club to push drugs on behalf of crimelord Tavernier (Francis Cosne). However Robert’s friend Dan Rover (Gianni Garko) – who’s been having an affair with Helene – is so enraged at her beating that he and mate Viletti (Michel Constantin) hatch a plan to assassinate Tavernier. But the hit draws the attention of two passing cops Barnero (Bernard Fresson) and Favenin (Michel Bouquet) and in an ensuing rooftop chase Barnero is shot dead by Viletti leading Favenin to swear vengeance.

Chilly and bleak cop thriller whose savage violence predates the not dissimilar Dirty Harry by a good year or so. But unlike Siegel’s film this really blurs the moral boundaries between hunter and hunted. At first the actions of Dan and Viletti in wiping out Tavernier – in no small part because of the impotence of the local police force to deal with him – seem entirely justified. Likewise, we enjoy Favenin’s ruthlessness as he corners two of Tavernier’s goons, cold-bloodedly shoots one of them dead and then threatens to frame the other for the murder unless the terrified man agrees to tell him who did the hit. But once Favenin turns his violent attentions to Rufus (Raymond Aulnay), a harmless man who supplied Dan and Viletti with an alibi for the night of the murder he begins to lose our sympathy. “Take a good look and never forget this” a bloodied Rufus tells the infant son who witnesses his Dad’s brutal beating, “That’s a cop for you.”

If that makes the film sound like a cop hating exercise, not at all, Blood On My Hands plays fair by both sides. “Barnero had kids too”, Favenin points out to Rufus. In fact both sides share a common enemy. Even as Dan lays plans for the hit cops Barnero and Favenin fret about the prospect of taking orders from Tavernier because he’s running for political office. And they get cold comfort from their ruthlessly pragmatic Chief of Police (Adolfo Celi) who advises Barnero that “The police are made to serve society as it may be, not to change it.” In a rare moment of dry humour Favenin tells Dan he’d actually like to congratulate him for murdering Tavernier!

The morality gets even greyer when Favenin breaks into Viletti’s apartment to kill him. In a sharp exchange Favenin rages at the man because his partner lost his life after firing a warning shot. Responds Viletti, “The other one didn’t know that, so he defended himself. You didn’t think about that did you? All in all, maybe your friend Barnero was the real bastard.” This is bracing stuff because it identifies an uncomfortable truth. Barnero did make a fatal misjudgement on that roof and Favenin is so blinded with rage he can’t see it. So by the time the climax rolls around, with Dan en route to Favenin’s country cottage and both men fuelled by bloodlust, you’re convinced the film is up for something wild. However the third act surprises with the knowledge of what he’s become weighing so heavily on Bouquet’s cop that he pens a full confession for the DA.

But when Helene turns up begging Favenin to clear Dan of Barnero’s murder charge, arguing not unreasonably that both men have gotten what they wanted, it’s already too late. Dan ends up shot full of holes by the local gendarmerie and with his dying breath mocks Helene for trusting cops, while Favenin’s confession turns him into a pariah amongst his fellow officers. Nobody wins. Both Garko and Bouquet have our sympathy as characters driven by loyalty and passion but in the end it doesn’t do either one any good. Favenin is done in by his conscience and Dan by his thirst for vengeance. Only Celli’s unprincipled boss – quite willing to bend whichever way the wind is blowing – comes out untouched. The film’s closing shot has Favenin framed through the window bars of his cottage, a symbolic prisoner of his own violent nature.

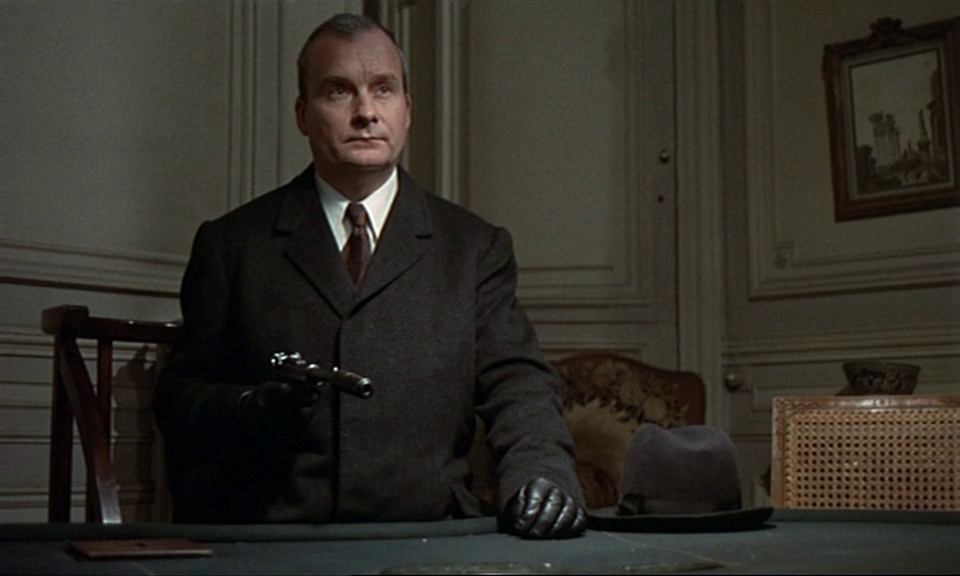

Boisset’s taut direction is well served by a good script and casting, atmospheric location shooting in the chilly autumnal countryside and bursts of brutally unvarnished violence. The sequence where Helene has the shit beaten out of her by Tavernier’s hoods is every bit as nasty as it sounds. It’s not a surprise to hear that the movie had pre-release censorship problems in France. As for performances the always reliable Michel Bouquet gives a characteristically internalised performance as the vengeful copper, one that effectively conveys both the rage driving him and the conscience that ultimately proves his undoing. It’s impressive that Bouquet’s short stature and dumpy frame are no impediment to this man’s threatening presence, even when he’s facing thugs two or three times his size. None of the other players get the depth of character granted to Bouquet’s Favenin but they all make a favourable impression.

Gianni Garko is a handsome and charismatic lead whose motives never seem less than credible although one could have wished for a bit more spark between his character and Francoise Fabian’s Helene. Adolfo Celi is enjoyably shifty as the police chief and I really liked Raymond Aulnay’s turn as Rufus. This meek and mild man instantly engages ones sympathy and makes you feel that if Dan has a guy like this in his corner then he must be okay. Best of all though is Michel Constantin’s hulking Viletti. Constantin has a palpable screen presence and his confrontation with Favenin – a scene imbued with the fatalism of a man who’s been waiting his entire life for death to come calling – is for me the highlight of the whole movie. I love the way Viletti puts on his hat after being ordered to by Favenin. In the quietly defiant way he adjusts it and smooths the brim down just so it’s as if Viletti is saying to his executioner, “Yeah, I know I’m going to die, but this is the way I’m going to look when I do!” Great stuff.