Last Updated on September 29, 2020 by rob

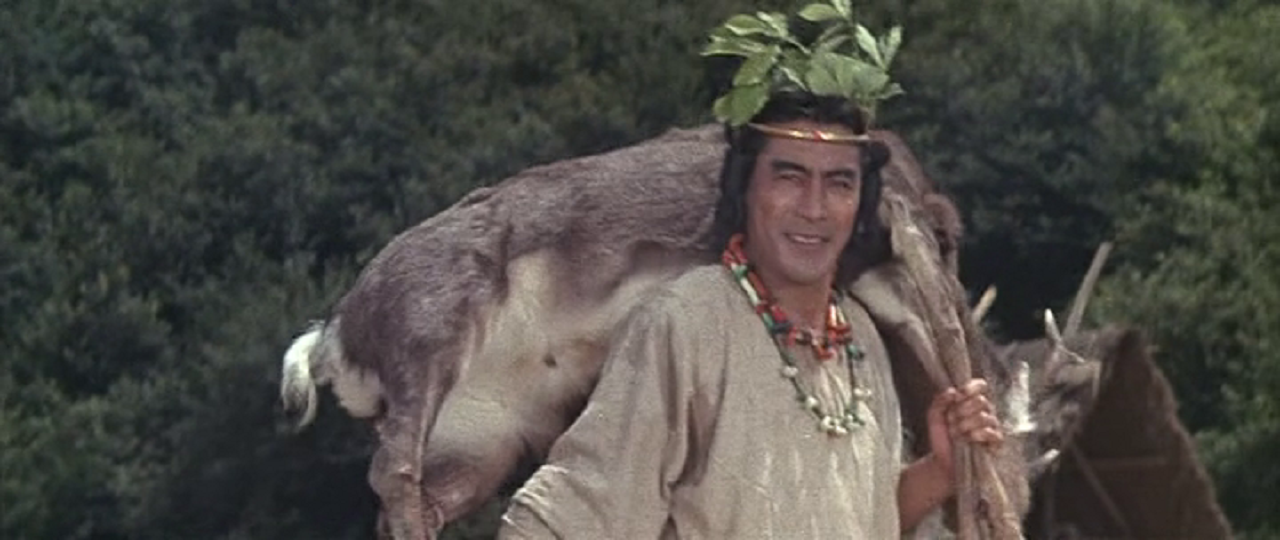

The Gods create Japan and their human offspring populate the country. But in the peaceful community of Ise, Prince Yamato’s (Toshiro Mifune) nephews led by Otomo (Eiijiro Tono) plot permanent exile for him so they can seize power. Ordered to fight a series of wars Yamato finds solace in the love of servant-girl-to-the-Gods Ototachibana (Yoko Tsukasa) and the legends of the Sun-Goddess Amarteratsu (Setsuko Hara) and her wayward brother Susanowa (Mifune again). Returning to Ise after surviving a violent typhoon at sea Yamato and his men are ambushed by Otomo’s army in a huge battle on the slope of Mt Fuji just as the volcano blows its top in a massive eruption.

Imagine a religious epic from Hollywood’s Golden Age crossed with one of Ray Harryhausen’s monster jobbies and you’ve got the starting point for Birth of Japan. A whopping 3 hrs in length and complete with intermission this Toho spectacular succeeds on pretty much every level because it’s a briskly-paced epic with both heart and vigour. The unfairness forced upon Mifune’s Prince Yamato by his scheming nephews, his yearning to return home to be with the woman he loves and his unhappiness at the way his victories in battle have turned him into both an object of fear and a target for assassination mean he has our sympathy right from the off. Even the romantic interludes between the Prince and the two ladies vying for his affections (Yoko Tsukasa and Kyoko Kagawa, both charming) – which are so often the bane of these kinds of movies – are poignantly played and never outstay their welcome.

Inagaki also brings some welcome characterisation to Yamato’s men, especially the wretched Yahara (Kichijiro Ueda), a servant who sees war as a way to enrich himself and who constantly runs afoul of a leader who really isn’t interested in the spoils of battle. The whole film feels remarkably fresh, in part because director Hiroshi Inagaki was – as his 6 hr plus Musashi Miyamoto (1954-6) samurai trilogy demonstrated – an old hand at this kind of epic storytelling. The script is very cleverly constructed in the way it tells two intertwining tales – the first about the birth of the Gods and the creation of Japan, the second following Prince Yamato’s odyssey – but cutting back and forth between the two so that no one storyline ever gets stale. The legends of Amarteratsu and Susanowa that we see dramatized here are designed in such a way they parallel Yamato’s emotional state, lifting his spirits and those of his men when they’re feeling down. So there’s also a point being made here about how a culture should never forget its past because it can draw from it the strength and encouragement to face an uncertain future.

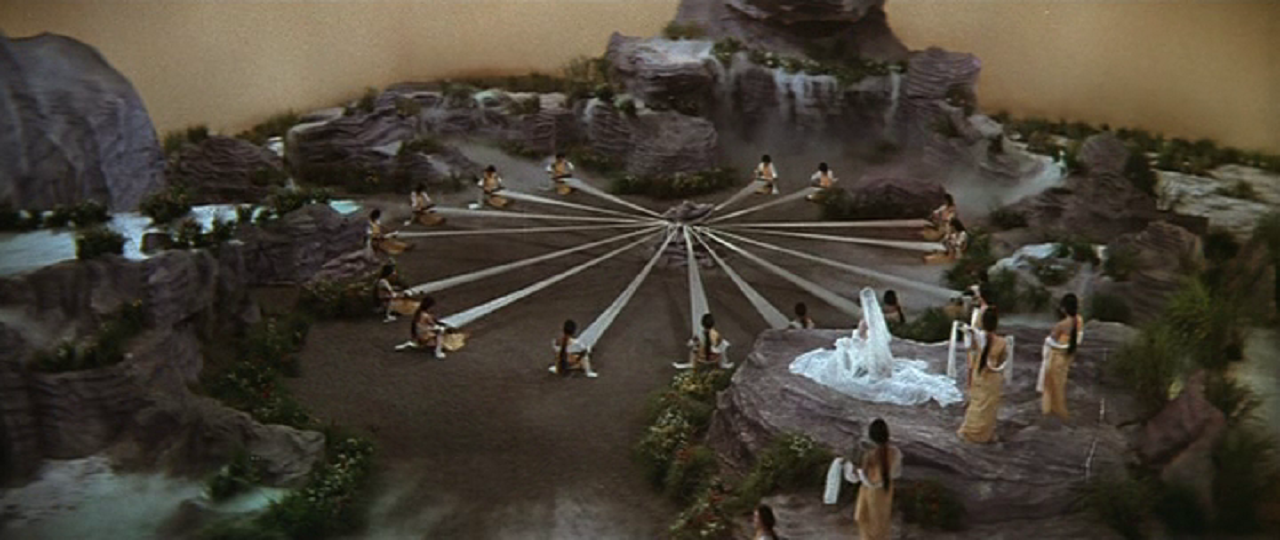

That’s especially true of the story of Setsuko Hara’s Sun Goddess, who retreats into her cave after a cruel trick played on her by her brother Susanowa. With everything plunged into darkness, on Earth and in heaven, the question for the other Gods (an amusingly puny looking bunch by Western standards it has to be admitted!) is how to get her out again. Because if she doesn’t come out everything will remain in eternal darkness. The solution turns out to be an ingenious combination of high artistry with low cunning and – lo and behold – the Sun Goddess emerges and once more the sun shines. Although these are Gods the point is that it’s human ingenuity not some Godly power that saves the day. Moreover, there’s an optimism coursing through Birth of Japan, a belief that the Japanese people are destined for great things.

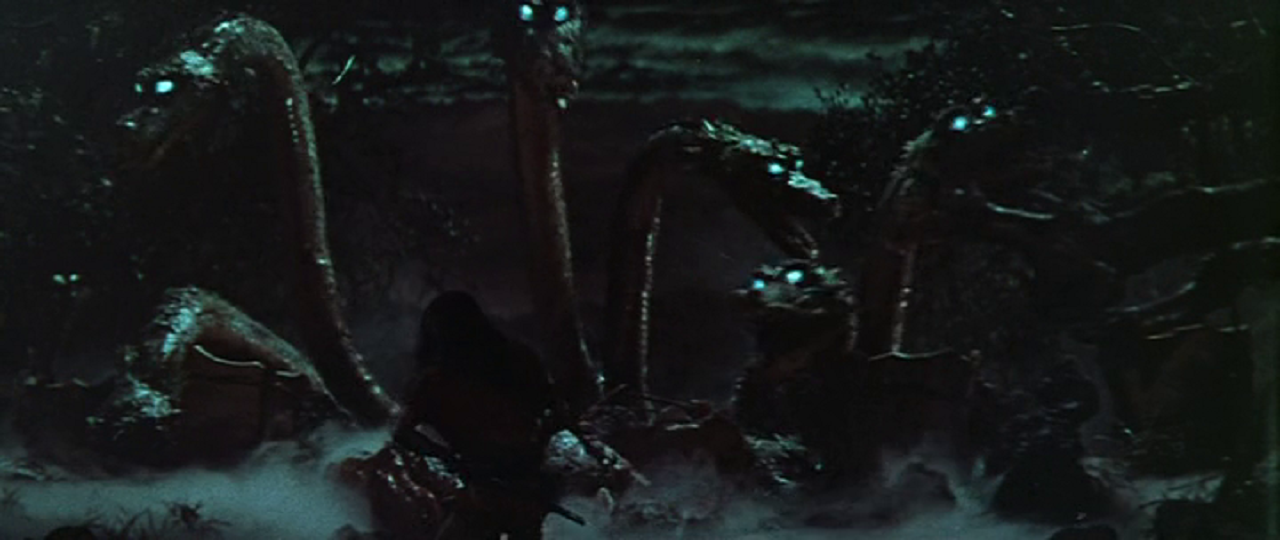

In its final shot the film makes explicit its message that if humans are descended from the Gods in the heavens then it’s the destiny of those who show compassion and consideration to others in their earthly lives to return to the heavens after death. Speaking of gods, Mifune’s other role here as the wild Susanowa, who slays an eight-headed dragon by first putting it to sleep with sake before killing it (a plot device reused, updated and paid loving homage to in the climax of 2016’s Shin Godzilla) is the actor at his most physically expressive and that’s what’s needed to sell the scene as the hydra is optically printed over Mifune’s exaggerated slashing motions. Eji Tsuburaya’s creature, complete with glowing eyes, is a great creation. It’s not a stop motion thing but a sort of puppet with the heads moved by wires and it looks splendid on screen. A full size tail section of the dragon has Mifune leaping onto it and stabbing away enthusiastically as vivid jets of blood come spurting out!

In almost any other movie this would be the centrepiece but Inagaki keeps upping the ante with ever more spectacular creations. A typhoon at sea is impressively realised, followed by a thrilling high-stakes battle on the slope of Mt Fuji and then to cap it all a spectacular volcanic eruption that has the enemy soldiers showered with burning coal, fried in vast lava flows and drowned when the lakes overflow and swamp the land. The special effects work here is generally excellent with a combination of model effects, live action and blue screen work. In fact some of it is so detailed that the only way I could tell I was looking at a model is because you can’t miniaturise flames or water. Otherwise it’s flawless.

There are some elaborate practical effects too. At one point during the climax the ground splits apart and swallows up a dozen fleeing soldiers! That’s a tough effect to pull off but it looks completely convincing. However there’s no getting away from the fact that the swordfighting and death scenes here are sometimes amusingly theatrical in style (it’s kind of the polar opposite of what Kurosawa was going for in his samurai movies of the period) and it’s matched by some of the plotting, e.g., the villainous Kumaso meets his end when he mistakes Mifune for a woman simply because the latter has disguised himself with a veil! Yet even as you laugh one is aware of a kind of old fashioned innocence that if you’re prepared to give it a chance exerts a genuine charm.

Part of this is of course the sheer spectacle of the thing. The film opens with a fantastic sequence of the Gods raising Japan from a bubbling, liquefied void. As the male and female Gods Izanagi and Izanami cross a rainbow bridge from the heavens to the newly formed continent we see them exploring a primordial landscape that’s been superbly visualised. This is followed by imaginatively conceived indoor sets on a huge scale (such as the King’s throne room at Ise), some huge outdoor ones and vast numbers of extras populating them. Toho must have spent a small fortune on this and it really shows in the production values. They certainly seem to have hired just about every actor and bit-player they could find.